La comunicación de los partidos políticos andaluces en Instagram: interactividad, temas y funciones

The communication of Andalusian political parties on Instagram: interactivity, topics, and purposes

- Elena Bellido-Pérez

- Antonio Pineda

- Ana I. Barragán-Romero

- Irene Liberia Vayá

- Palabras clave:

- Comunicación Política

- Propaganda

- Partidos Políticos Andaluces

- Interactividad

- Keywords:

- Political Communication

- Propaganda

- Andalusian Political Parties

- Interactivity

1 Introduction

Instagram has emerged as a relevant platform for the study of election campaigns (Filimonov et al., 2016). Even though the literature shows a certain body of results regarding political strategies and communication on this social networking site (henceforth, SNS), scientific research on Instagram is still limited compared to the abundant production focused on social sites such as Facebook and Twitter—in fact, Twitter is the SNS which has attracted most scholarly attention, and it is considered the political SNS par excellence (Enli & Skogerbø, 2013; Filimonov et al., 2016; García Ortega & Zugasti Azagra, 2014). In the particular case of Spain, a country where social media have become a fundamental tool for political communication (Ruiz del Olmo & Bustos Díaz, 2016), academic publications regarding the political use of Instagram have been, however, scarce (Selva-Ruiz & Caro-Castaño, 2017).

Moreover, research on Instagram political communication tends to focus on candidate profiles, and rarely on political party accounts. Another shortcoming of existing literature is that most research is conducted within national contexts, hence neglecting the study of political communication in regional or local contexts. Given this state of affairs, this paper aims to enhance the knowledge on SNS political communication by focusing on the Instagram behaviour of five mainstream political parties from the Spanish region of Andalusia. Our main research objectives are to analyse whether the Instagram profiles of Andalusian parties are truly interactive—hence leading parties to making a connection with, and responding to, citizens—as well as the main themes and purposes fulfilled by their posts. To do so, it is necessary to review first the main findings regarding Instagram political use, as well as the theory of SNS interactivity.

2 Literature review and theoretical framework

Studies related to political communication on Instagram point to the increasing importance of candidates on this SNS (Grusell & Nord, 2020; Turnbull-Dugarte, 2019; Pineda et al., 2022). A study by Mireille Lalancette and Vincent Raynauld (2017) regarding Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau concluded that the politician’s images were part of a growing personalisation campaign. There is also a certain level of interest in associating the image of the “ideal candidate” with familiar, personal traits, as evidenced by Caroline Lego Muñoz and Terri L. Towner (2017) in their analysis of US primaries. In Sweden, Kirill Filimonov et al., (2016) found that candidates had a strong visual presence, yet did not reveal much about their private lives, but instead showed settings related to their professional life. Similarly, a study by Mattias Ekman and Andreas Widholm (2017) regarding the sixteen Swedish political Instagram profiles with the most followers showed a lack of images related to the politicians’ private lives. In any case, it seems that a candidate’s prominence generates more engagement than other types of images on Instagram; this has been shown by Yilang Peng’s (2021) analysis of images of US candidates, which concludes that the audience tends to react positively to images where a politician’s face is identified, and specifically where the politician expresses some emotion.

Regarding the country we are focusing on, Spain, accumulated knowledge indicates some trends in candidate representation as well. Pablo López-Rabadán and Hugo Doménech-Fabregat (2018, p. 1026) report that the image projected by leaders on Instagram during the Catalan independence conflict reflected, among other aspects, an “intense dynamic of personalisation” and a “positive emotional appeal”. In their study on Spanish representatives, David Selva-Ruiz and Lucía Caro-Castaño point out that new political parties such as Podemos (We can) and Ciudadanos (Citizens) use Instagram in a way that is more personalised than that of traditional parties, yet “even though there are many publications characterised by proximity and informality, there is still a certain rigidity typical of other media” (2017, p. 913). In a similar vein, a study carried out one year before the 2016 election regarding Ciudadanos’s former leader Albert Rivera, shows that most publications referred to his work as a politician, yet 20% showed his more personal side (Verón Lassa & Pallarés Navarro, 2017). During the 2015 and 2016 general elections, Raquel Quevedo-Redondo and Marta Portalés Oliva (2017) found that, as elections approached, candidates increased the number of posts as an ongoing campaign strategy and noted that presidential candidates published seven times more personal-emotional posts than those involving a call-to-vote. Also, regarding these elections, Silvia Marcos García and Laura Alonso Muñoz (2017) found that content in private or personal contexts is nearly non-existent on the accounts of the main national political parties and their respective leaders, yet at the same time, the purpose of humanising politics is a priority. Nevertheless, more recent research suggests that Spanish candidates show a more professional, less humanised profile on Instagram (Bellido-Pérez & Gordillo-Rodríguez, 2022).

Personalisation is not the only variable analysed in the Instagram literature. Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte (2019) studied the use of Instagram by Spanish parties during the 2015 and 2016 elections and concluded that the most highly promoted candidate of the four main figures was Rivera, with new parties Podemos and Ciudadanos being the most efficient in terms of engagement, both on party and candidate profiles. In terms of the posts’ purposes, none of the parties used Instagram as a way of systematically communicating their policy positions, and Podemos was the only one that was more likely to use it to mobilise its voters and gain support. However, Antonio Pineda et al.’s (2022, p. 1151) analysis of the profiles of Spanish candidates in the 2018 Andalusian election partially contradicts Turnbull-Dugarte’s results: the former found that new parties use Instagram to a lesser extent than traditional parties. In fact, there is a clear ideological distinction in this regard, as the political right publishes more often than the left. Also, regarding new politics and parties, Vox has been studied by Eva Aladro Vico and Paula Requeijo Rey (2020) pertaining to its Instagram activity in the 28 April 2019 general election. The authors point out that the main issues addressed by Vox two months before the election focused on the subjects of danger-enemy, separatist nationalism, feminism, Islam, immigration, and women. On the other hand, according to a study by John Parmelee and Nataliya Roman (2020), posts by leaders who are ideologically similar to the users who participated in the survey on which their study was based, are the main influence on their opinions. Additionally, some Instagram-related studies performed in recent years (Pineda et al., 2020; Russmann and Svensson, 2017; Verón Lassa and Pallarés Navarro, 2017) confirm that political parties are still not taking advantage of the interactive capabilities of SNSs—a hint which leads us to the theoretical framework of our research.

The theory used in this article relies on the concept of interactivity applied to SNS communication. Interactivity is a media-specific feature of ICT (Vergeer et al., 2011) as well as a recurrent element when considering the political opportunities of the Internet. In fact, theorising on the web’s political possibilities has revolved around concepts such as proximity, dialogue, and horizontal relationships. The idea of a potential increase in direct voter contact (Powell & Cowart, 2003), or the perception of the web as a development that facilitates participation and engagement in the political process (Bekafigo & McBride, 2013; Vergeer et al., 2011), can be connected to the notion of open and equal deliberation, which is linked to techno-enthusiasm (Loader & Mercea, 2011)—as early as the year 2000, Jennifer Stromer-Galley referred to the Internet as a “magic elixir” toward which scholars looked in order to “reinvigorate the masses to participate in the process of government” (2000, p. 113). The techno-optimist perspective somehow persisted in later publications, where it was stated, for example, that SNS comments comprise a tool leading to more participatory politics (Serfaty, 2012). Indeed, in a context in which web 2.0 applications are seen “as providing new opportunities to positively increase dialogue between people” (Vergeer & Hermans, 2013, p. 400), SNSs have an inherent potential to provide horizontal communication and user-generated content, thereby distancing themselves from traditional mass communication and favouring one-to-one engagement.

Pertaining to online political communication, interactivity is believed to exist when there is dialogue between public representatives and citizens beyond the simple transmission of information, or, in other words, “user-to-user interaction” (Small, 2011, p. 887), which, according to Darren G. Lilleker (2016), is the most attractive and democratic type of interactivity. In any case, the literature has categorised the interactive possibilities offered by the internet to political communication. Sally J. McMillan (2002a) uses expressions such as user-to-system, user-to-document, and user-to-user; focusing on the latter, she proposes four types of interactivity: monologue and feedback (both of which are one-way communication); responsive dialogue and mutual discourse (both two-way communication) (McMillan, 2002b). S. Shyam Sundar, Sriram Kalyanaraman and Justin Brown (2003) propose the concepts of both functional and contingency views. The former refers to the web’s ability to facilitate dialogue through diverse functions, but not to how this is carried out; the contingency view distinguishes three levels: (1) two-way/non-interactive communication, when messages flow both ways; (2) reactive communication, when messages respond to immediately preceding messages; and (3) interactive/responsive communication, when messages relate to several messages preceding them. A few years later, Paul Ferber et al., (2007) broadened this model by adding a third user, from which they suggest two additional modes: controlled response and public discourse, the latter being the highest expression of interactivity. Based on this proposal, Lilleker (2015) developed a scale from 1 to 10 to measure the level of interactivity of a website on the grounds of the audience’s control of the message. In the specific context of SNSs, Pablo López-Rabadán and Claudia Mellado (2019) developed a useful classification based on the level of interactivity: at the lowest level is the approach strategy, which includes mechanisms like hashtags and links; at the intermediate level is the invitation to dialogue, with actions such as liking, retweeting, and mentioning; at the highest level is dialogue itself, which refers to a conversational exchange between users where a coherent dialogue is developed through mentions.

3 Research aims and questions

Taking into account the literature review and theoretical framework, our paper aims to fill three research gaps. First, the fact that most research deals with the image of candidates on Instagram; hence, our paper analyses whether political parties, instead of individual politicians, establish interactive communication with their audience.

Second, our study attempts to fill a gap regarding the analysis of political interactivity on Instagram, which still remains scarce (Pineda et al., 2022), particularly in comparison with candidate representation.

Third, by focusing on a regional political context, our research fills a gap in the literature on Instagram use, since most research is conducted within a national context. In order to do so, the Spanish region of Andalusia has been chosen as context: Andalusia is Spain’s most populous region—in 2020, it had a population of 8,464,411 inhabitants of a total of 47,450,795 people in the entire country, nearly a fifth of the national population (Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE], 2020)—and it is characterized by a quite widespread SNS use: 64.6% of the population are digital users, hence being above the national average (63.2%) (INE, 2022). In particular, Instagram is a key platform in Andalusia: Málaga and Seville are among the five Spanish cities with more Instagram profiles (The Social Media Family, 2020)—a practice which is especially popular among young people: Andalusians below 18 use Instagram more than any other platform (Consejo Audiovisual de Andalucia [CAA], 2020). Thus, the fact that parties are interested in reaching both current and future voters may explain why it is important to study Instagram regarding Andalusian politics. Besides, Andalusia is politically noteworthy, since it is currently composed of a multi-party political system resulting from the rise of new parties and coalitions since 2014. Moreover, at the 2018 regional election, it was the first Spanish community to bring radical-right party Vox into parliamentary politics—besides ousting the Socialist government from power, which had ruled the region for decades: after the election, a coalition formed by the conservative Partido Popular (Popular Party), the right-libertarian Ciudadanos, and national-populist Vox, governed the region for a period and established a formula which was later replicated in other autonomous communities.

To approach the analysis of Instagram dialogical use by Andalusian parties, our secondary objectives pertain to interactivity, topics, and purposes of political posts, hence aiming to observe whether there is true dialogue with citizens (or failing that, an approximation to dialogue), and whether parties communicate in order to get closer to citizens.

These objectives—as well as theoretical distinctions regarding interactivity levels (López-Rabadán & Mellado, 2019)—lead us to formulate the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1. Which Andalusian political parties use Instagram most frequently?

RQ2. Is there genuine dialogue with citizens through the Instagram profiles of Andalusian parties?

RQ3. Are there differences between Andalusian parties regarding the use of mechanisms for inviting dialogue on Instagram?

RQ4. Are there differences between Andalusian parties pertaining to the use of mechanisms for approaching dialogue on Instagram?

RQ5. Which topics are most used in Andalusian parties’ Instagram communication?

RQ6. Which are the main purposes of Andalusian parties’ Instagram posts?

On the grounds of literature indicating a low level of SNS political interactivity in Spain (Cebrián Guinovart et al., 2013; Criado et al., 2013; Pineda et al., 2021; Ramos-Serrano et al., 2018; Zugasti Azagra & Pérez González, 2015), and on Instagram in particular (Pineda et al., 2022; Verón Lassa & Pallarés Navarro, 2017)—a scarcity of Instagram dialogue which is also found in countries like Sweden (Russmann & Svensson, 2017)—the following hypothesis (H) can be formulated as an answer to RQ2:

H1. Andalusian political parties do not use Instagram in an interactive way.

4 Method

Instagram has been chosen as an object of research and sampling mainly due to its extraordinary popularity: with two billion active users per month (The Social Media Family, 2022), it provides an enticing audience for politicians. Moreover, this SNS has experienced the strongest growth in Spanish political communication, ranking second among the most consulted sites with a share of 51.2% (AIMC, 2019). According to The Social Media Family (2022), Instagram is also preferred by young people, as 64.17% of Instagram’s Spanish users are between 18 and 39 years of age. It is also the most trusted SNS among university students as well (Shane-Simpson et al., 2018). As Spanish politicians have been courting young voters through SNSs for years by adopting a trend that started with Obama’s 2008 campaign (García Orta, 2011), using Instagram is simply another step forward in this regard. Another factor that makes Instagram an interesting site is its semiotic nature, characterised by the predominance of images over text, which further enhances its ability to personalise parties and give more space to emotional communication.

Quantitative content analysis—which has already been utilised to study political messages on Instagram (Bast, 2021)—is used as data-gathering technique (Krippendorff, 2004). Operationalisation of analytical variables focuses on quantifying the number of posts made by each party, the topics covered in the posts, the main purposes served, and a series of variables related to party-citizen interactivity. The latter have been operationalised on the basis of work by José Juan Verón Lassa and Sandra Pallarés Navarro (2017), Manuel Jesús Cartes Barroso (2018), and principally, López-Rabadán & Mellado (2019), with their distinction between high, intermediate, and low interactivity. Among these, the @-reply resource works as the basic indicator of interaction, a type of response that has already been used as an indicator of dialogue in SNSs in general (Ahmed & Skoric, 2014; Cebrián Guinovart et al., 2013; Criado et al., 2013; Zugasti Azagra & Pérez González, 2015)—and in Instagram in particular (Pineda et al., 2022)—and has been found to be the highest level of interactivity and dialogue (López-Rabadán & Mellado, 2019). To measure dialogue, we have also used two variables with a low level of interactivity: firstly, the presence and number of hashtags and links, which indicate a strategy for approaching dialogue; secondly, a medium-level interactivity variable: the number of mentions—a resource that corresponds to the invitation to dialogue (López-Rabadán & Mellado, 2019).

Making topics and purposes operational has relied on the analytical work of Todd Graham et al., regarding SNSs and politics (2013)—this study, related to the British context, has also been taken into account when operationalising interactivity-related variables—in addition to categories derived from Aladro Vico and Requeijo Rey’s work (2020) on Instagram in Spain, and Francisco Javier Ruiz del Olmo and Javier Bustos Díaz’s (2016) on political communication, in order to adjust our analytical construct to the Spanish context. For a complete list of the categories that make up the interactivity, thematic content, and purposes variables, see Tables 2-5.

This analytical construct has been applied to a sample of posts collected from the official Instagram profiles of the five parties which had parliamentary seats in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia in 2020. To begin with, Partido Popular Andaluz (Andalusian Popular Party, PP-A), which governs Andalusia from 2019 as the regional branch of the national Partido Popular (PP)—a 1989 re-foundation of Alianza Popular (People’s Alliance), which was originally founded in 1976 by post-Francoist proto-parties. Today, it stands as a traditionalist conservative party. The second most powerful Andalusian party is center-left Partido Socialista Obrero Español de Andalucía (Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party of Andalusia, PSOE-A), the regional branch of the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, PSOE), which is the oldest Spanish political party. PSOE-A ruled Andalusia for a very long time (1978 to 2019), and it is ideologically progressive and pro-European. New parties include, on the one hand, right-wing libertarian Ciudadanos Andalucía (Citizens Andalusia, Cs-A), the Andalusian branch of national party Ciudadanos (Citizens), which was founded in 2006 as a Catalonian anti-independentist party. Although it was marketed as centrist, Ciudadanos tried to lure libertarian-conservative voters, and moved to the right—in fact, Cs-A governed Andalusia with the PP-A between 2019 and 2022. Another rising party is nationalist-populist radical-right Vox-Andalucía (Vox-Andalusia, Vox-A), the regional arm of Vox, which was founded in 2013 and entered the Spanish parliament in 2019, right after entering the Andalusian parliament that same year—what is more, Vox-A supported the PP-A/Cs-A coalition after the 2018 Andalusian election, being the first time a government was supported by the far-right after the restoration of democracy in Spain. The fifth political force in our sample is left-wing electoral coalition Adelante Andalucía (Andalusia Forward, Adelante-A), which comprises several organizations, of which we will focus on the three most important. First, left-wing party Podemos Andalucía (We Can Andalusia, Podemos-A), the Andalusian division of parent organization Podemos (We Can)—a left-populist party founded in 2014, which experimented a very quick rise, and even co-governed Spain between 2019 and 2023 with the PSOE and other leftist parties. Second, communist-leaning party Izquierda Unida Andalucía (United Left Andalusia, IU-A)—national-level organization Izquierda Unida (United Left, IU) is a political coalition founded in 1986; alongside Podemos, it joined the 2019-2023 progressive Spanish government. Third, hard-left environmentalist-socialist movement Anticapitalistas Andalucía (Anti-capitalists Andalusia, Anticapitalistas-A) belongs to a Spanish movement founded in 1995; despite joining Podemos in 2015, Anticapitalistas has worked as an independent party since 2020.

The aim of this multi-party selection was to avoid the traditional Andalusian two-party system by including both new and old organisations, and to highlight the sample’s ideological diversity, including parties occupying the anti-capitalist portion of the political spectrum (e.g. Anticapitalistas-A), traditional conservatives (PP-A), centrist social-democrats (PSOE-A), centre-right libertarians (Cs-A), progressive leftists (Podemos-A), and radical-right national-populists (Vox).

From the official profiles of these parties—@psoedeandalucia, @ppandaluz, @ciudadanosandalucia, @andalucia_Vox, @adelanteandalucia, @podemos_and, @iuandalucia and @Anticapi_andalucia—we collected the 1,805 posts that were published throughout 2020, hence comprising the total universe of posts during the study’s time frame—in this sense, sampling periods that go beyond specific electoral contexts fit well with a research object like SNSs, which imply a continuous communication effort during non-election periods as well1. Furthermore, and regarding context, this study covers the entire year of 2020, a period characterised by the global pandemic caused by COVID-19 in which SNSs became a primary source of information for citizens, and gave them a voice to communicate their fears and doubts in the face of an unprecedented health emergency.

After carrying out a first two-coder test conducted by a postgraduate student and a PhD research assistant, most of the tested variables yielded a maximum average reliability index (α = 1, applying Krippendorff's alpha2), with the exception of the presence of links (0.62), mentions (0.72), and purpose (0.74) variables. Since these variables were below what is usually considered minimum reliability standards in content analysis (α = 0.80), a second two-coder test was conducted after a meeting in which coders received additional instructions on variable interpretation. As a result, almost all abovementioned variables obtained an average reliability of α = 1, with the @mentions variable obtaining α = 0.82. Coding was performed by a PhD research assistant who had received specific training, and who also collected the posts manually under the supervision of the authors of this paper. The data was collected and coded between 22 June and 27 December 2021.

5 Results

The frequency of publication of each party can be seen in Table 1, where Vox, with 483 posts, is the party that published most on Instagram in 2020, whereas traditional party the PSOE-A, posted the least (89). Near the middle of the table, right-wing parties such as (Cs-A) and those of the left-wing (Anticapitalistas-A, Adelante-A), have similar posting frequencies (around 8%).

| Party | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Vox | 483 | 26.8 |

| Podemos Andalucía | 353 | 19.6 |

| Partido Popular Andaluz | 289 | 16.0 |

| Anticapitalistas Andalucía | 157 | 8.7 |

| Adelante Andalucía | 155 | 8.6 |

| Ciudadanos Andalucía | 153 | 8.5 |

| Izquierda Unida Andalucía | 126 | 7.0 |

| PSOE de Andalucía | 89 | 4.9 |

| Total | 1805 | 100 |

Table 1

Number of posts (frequency and percentages)

Regarding interactivity, we have taken into account both the basic indicator of interaction in SNSs, or in other words, the direct response to users regarding the comments of the post through the @-reply and other secondary indicators of interactivity, like the presence of hashtags, links, and mentions (Table 2). According to the results of replies to comments, Andalusian parties show an overwhelmingly strong, zero level of interactivity with their Instagram followers: there is a complete absence of replies to users’ comments from all parties.

| Party | @-replies | Mentions | Hashtags | Links |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vox | 0 | 899 | 2,701 | 0 |

| Podemos Andalucía | 0 | 350 | 281 | 76 |

| Partido Popular Andaluz | 0 | 181 | 3,869 | 0 |

| Ciudadanos Andalucía | 0 | 161 | 257 | 0 |

| IU Andalucía | 0 | 25 | 254 | 1 |

| Adelante Andalucía | 0 | 18 | 53 | 2 |

| Anticapitalistas Andalucía | 0 | 11 | 312 | 2 |

| Total | 0 | 1,681 | 7,859 | 81 |

Table 2

Interactivity indicators (frequencies)

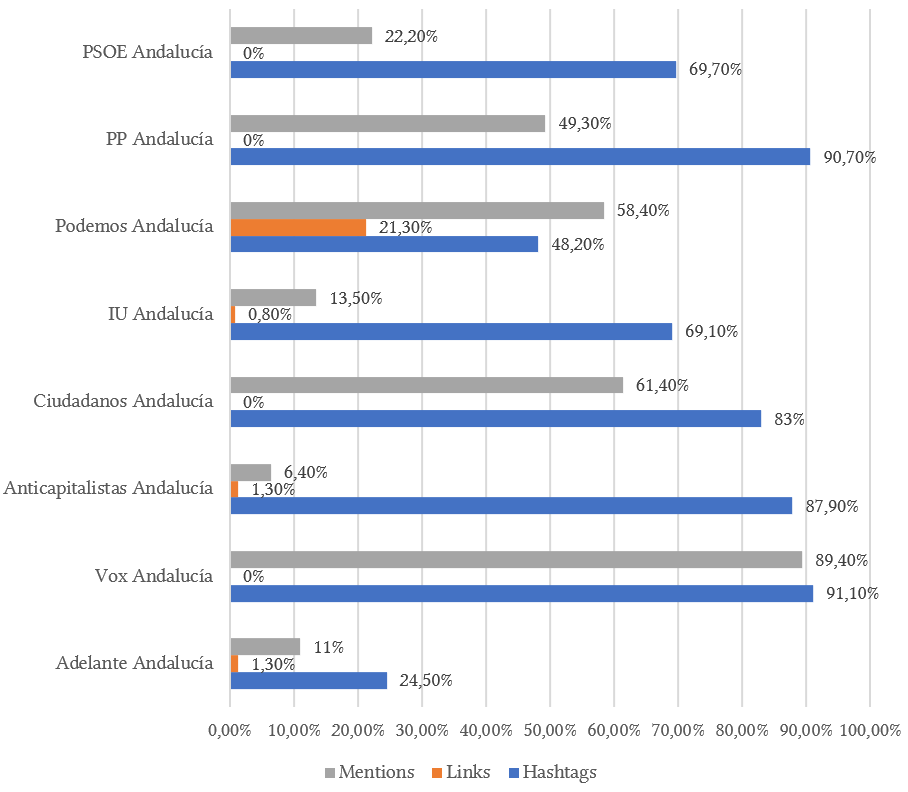

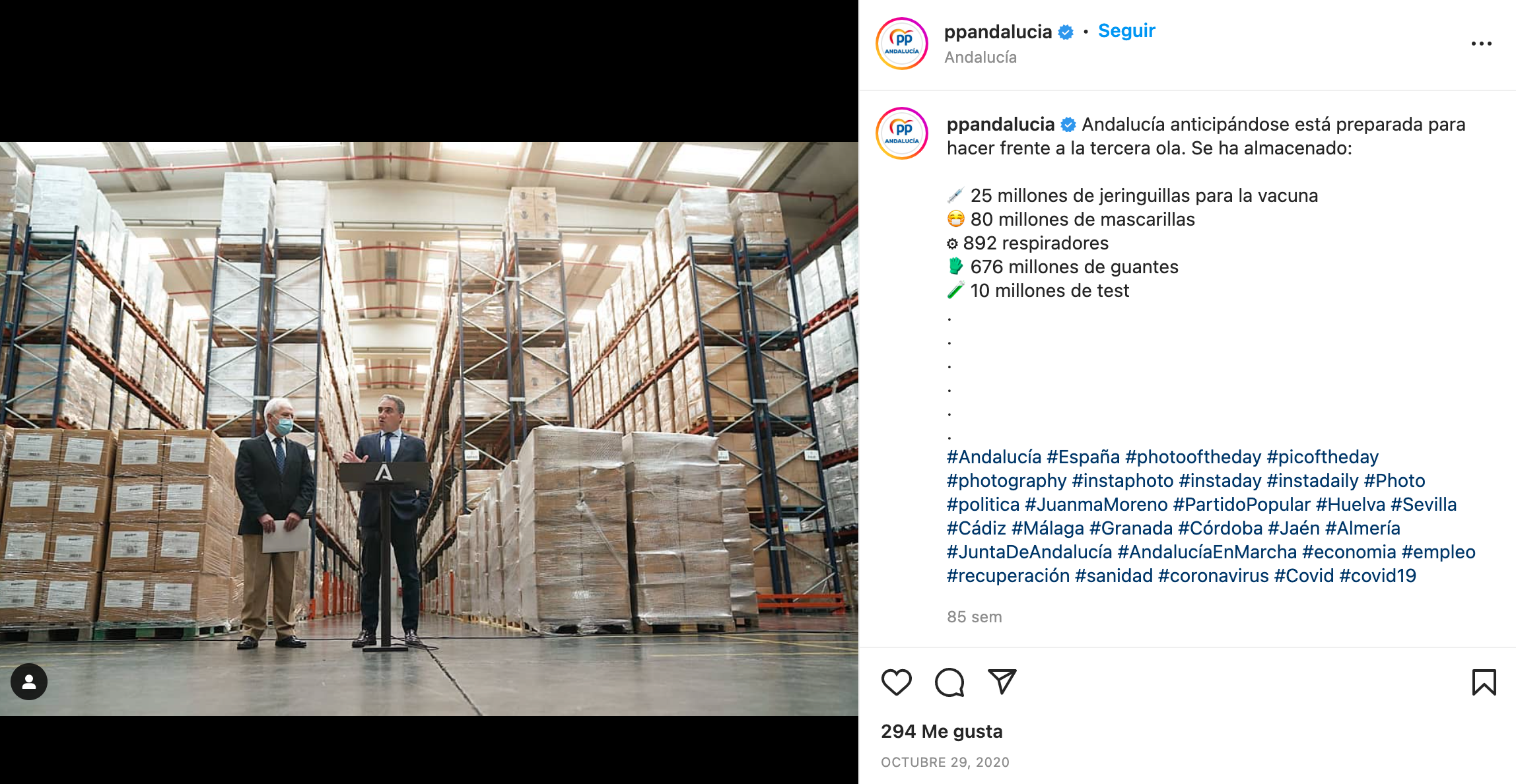

According to what López-Rabadán & Mellado (2019) classify as mechanisms for approaching dialogue (the lowest level of interactivity), such as hashtags and links, the vast majority of posts contain hashtags. We can observe this tendency in Figure 1, which indicates the percentage of posts using one of these mechanisms over the total of a party’s publications. However, hashtags are not popular in the cases of two left-wing parties: Adelante-A, where 75.5% of the posts were published without hashtags, and Podemos-A, with 51.8% of publications lacking this resource. On the opposite side of the ideological spectrum, the high number of posts with hashtags by radical-right Vox stands out (91.1%), closely followed by the conservative PP-A (90.7%). Moreover, and as Table 2 indicates, the PP-A is also the party with the highest total number of hashtags, 3,869, more than a thousand hashtags more than Vox.

To exemplify the large number of hashtags used by the PP-A, Figure 2 shows a post about the measures taken to mitigate the third wave of the coronavirus, which contains 29 hashtags.

Figura 1

Use of hashtags, links, and mentions (percentages).

Figura 2

(PP de Andalucía, 2020).

It is also worth mentioning the huge quantitative leap between these right-wing parties and the party with the third highest number of hashtags: far-left Anticapitalistas-A, with only 312. With regard to links as a mechanism for approaching dialogue, their use is very limited, as only four of the eight parties analysed ever used them—Adelante-A, Anticapitalistas-A, IU-A, and Podemos-A; all of them left-wing. Podemos-A stands out among them, using links in 21.3% of its posts. Pertaining to mentions as a mechanism for inviting dialogue, Vox is the party that used this resource the most (on 899 occasions), followed far behind by Podemos-A (350). Figure 1, which comparatively depicts the use of these resources in detail, shows a certain uniformity in the accounts of parties such as Cs-A, Podemos-A and PP-A, which have used mentions in nearly half of their publications. The other parties tend not to use them frequently, except in the case of Vox, as pointed out above.

When analysing mentions, it was also considered whether this tool appeared as a simple tag in the text of the post, or whether it was accompanied by a comment, link, or hashtag. As Table 3 shows, mentions with a comment are the most frequent, accounting for more than half of the 1,681 total mentions. Again, Vox is the party that uses the most mentions + comments, followed by Podemos-A, while the parties using this resource the least, all belong to the left. Vox also stands out for using the mention + hashtag combination, followed on this occasion by Ciudadanos-A. As for links, almost no party uses them together with mentions.

| Party | Mention + commentary |

Mention + link | Mention + hashtag |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vox | 495 | 2 | 155 |

| Podemos Andalucía | 203 | 0 | 0 |

| Partido Popular Andaluz | 132 | 0 | 31 |

| Ciudadanos Andalucía | 89 | 2 | 72 |

| Adelante Andalucía | 17 | 0 | 1 |

| PSOE de Andalucía | 16 | 0 | 12 |

| Izquierda Unida Andalucía | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Anticapitalistas Andalucía | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 977 | 4 | 271 |

Table 3

Mentions with comments, links, and hashtags (frequencies)

Regarding topics (Table 4), four themes stand out above the rest by a considerable margin, the most prominent being “economy and business”, which represents 21.6% of the total number of topics in all profiles. In second place is “health and social welfare” (11.7%); in third place is “government” (10.2%); and fourth place is held by the “campaign and/or political parties” topic (8.8%). Posts with undetermined topics were also frequently found (10.9%), along with social issues such as gender/feminism, education, and human/civil rights, although in lower proportions. On the other hand, the fact that the topic of ‘Andalusia’ barely obtained 5% of the total number of posts, indicates that in 2020, Andalusian nationalism was still weak among parties.

| Topic | Adelante-A | Vox | Anticapi-talistas-A | Ciudada-nos-A | IU-A | Pode-mos-A | PP-A | PSOE- A | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economy and business | 20 | 36.9 | 8.9 | 32 | 16.7 | 13.6 | 14.1 | 7.9 | 21.6 |

| Health and social welfare | 14.2 | 10.4 | 14 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 11.7 | 20.2 | 11.7 |

| Government | 7.7 | 12.4 | 3.2 | 6.5 | 12.7 | 8.8 | 11.7 | 19.1 | 10.2 |

| Campaign and/or parties | 5.8 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 13.1 | 6.3 | 12.8 | 17.2 | 2.2 | 8.8 |

| Gender/feminism | 8.4 | 1.9 | 17.2 | 0.7 | 6.3 | 13.4 | 2.4 | 10.1 | 6.7 |

| Education | 6.5 | 6.2 | 4.5 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 9.1 | 4.5 | 7.9 | 6.6 |

| Andalusia | 5.2 | 0.6 | 7 | 5.9 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 9.7 | 11.2 | 5 |

| Human/civil rights | 5.2 | 2.7 | 8.9 | 2 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 0.3 | 3.4 | 3 |

| Environment | 3.9 | 1 | 7 | - | 3.2 | 4.3 | 1.4 | - | 2.5 |

| Culture | 4.5 | 1.9 | - | 1.3 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 0.7 | - | 1.6 |

| Immigration | 0.6 | 3.9 | 3.2 | - | - | 0.6 | 0.3 | - | 1.6 |

| Conflict and war | 1.3 | 0.2 | 1.9 | - | 10.3 | 2.3 | - | - | 1.5 |

| Monarchy | 3.2 | - | 3.2 | - | 4 | 1.4 | 2.1 | - | 1.4 |

| Corruption | 0.6 | 1 | - | 1.3 | 1.6 | 2 | - | 2.2 | 1.1 |

| The media | - | 2.7 | - | - | 0.8 | 0.6 | - | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Infrastructure | - | 1 | - | 2 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1 | - | 0.9 |

| Spain | - | 1 | - | 0.7 | - | - | 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.7 |

| Defence/military | - | 0.6 | 0.6 | - | - | 0.3 | 2.1 | - | 0.6 |

| Animal rights | 0.6 | 0.4 | - | - | - | 1.7 | - | - | 0.5 |

| Other | 3.2 | 2 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 2 | - | 2.3 |

| Undetermined | 9 | 9.3 | 12.7 | 15 | 12.7 | 5.1 | 16.6 | 13.5 | 10.9 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Table 4

Topics of the posts (percentages)

Focusing on specific parties, the main topic of economy and business features prominently in Vox’s profile (36.9%); a focus which is illustrated by Figure 3, where the party’s representative talks about unfair competition in supermarkets during the pandemic. It happens the same in the case of another pro-business party, Ciudadanos-A (32%); proportionally, no other party has devoted so many publications to a specific topic. Moreover, this theme is addressed most often by all of the parties, except for three: Anticapitalistas-A, PP-A, and PSOE-A. In the first, gender/feminism stands out; in the second, the “campaign and/or political parties” topic; in the third, “health and social welfare”.

Figura 3

(VOX Parlamento de Andalucía, 2020).

Finally, with regard to the posts’ purposes (Table 5), “taking a position / party stance” is the main function (47.6% of the total), with a notable difference compared to the rest of purposes, and among all the parties as well—except for the PSOE-A, where it takes second position (22.5%), due to the fact that the aim of “criticising/discussing an issue” predominates in this progressive party (32.6%). The organisation that most often uses the “taking a position/party stance” purpose is Adelante-A (72.9%), followed by Anticapitalistas-A (70.1%). This propagandistic purpose is clearly visible in posts like Figure 4, where Adelante-A takes a politically republican stance and attacks the Spanish monarchy, explicitly stating that Andalusia has no King.

| Purpose | Adelante-A | Vox | Anticapi-talistas-A | Ciudada-nos-A | IU-A | Pode-mos- A | PP-A | PSOE-A | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taking a position / party stance | 72.9 | 52.2 | 70.1 | 52.9 | 39.7 | 34.4 | 39 | 22.5 | 47.6 |

| Taking a position / stance of an individual politician | 7.1 | 22.8 | 4.5 | - | 0.8 | 32.7 | 14.1 | 19.1 | 16.7 |

| Highlighting achievements | 5.2 | 5 | 0.6 | 27.5 | 26.2 | 10.5 | 19.3 | 11.2 | 11.7 |

| Criticising / discussing an issue | 11 | 6 | 0.6 | 2.6 | 7.9 | 7.1 | 10.3 | 32.6 | 8 |

| Acknowledgement / recognition | 3.2 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 11.8 | 17.5 | 2.8 | 8.3 | 11.2 | 5.8 |

| Party activities | - | 10.1 | 15.3 | - | 3.2 | 6.8 | - | - | 5.7 |

| Giving advice / helping | - | 0.2 | 1.3 | 3.9 | - | 1.4 | 3.4 | - | 1.3 |

| Referring to a news item | - | - | 3.8 | - | 1.6 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1 |

| Other | - | 0.6 | 0.6 | - | - | - | 0.7 | - | 0.4 |

| Undetermined | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 1.8 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Table 5

Purposes of the posts (percentages)

The second most frequently purpose on Instagram is widely distributed according to the party in question: for Vox and Podemos-A, it is “taking a position / stance of an individual politician”. Moreover, since there is such a high number of posts concentrated among these two parties, it is the second most frequent function among all political forces; for Ciudadanos-A, IU-A and PP-A, it is “highlighting achievements”, and for Anticapitalistas-A, “party activities”. Strikingly, this last purpose is quite scarce, or even non-existent, in almost all the parties, with the exception of radical-left Anticapitalistas-A and radical-right Vox.

Figura 4

(Adelante Andalucía, 2020).

6 Discussion and conclusions

Pertaining to the research questions regarding the interactive and communicative behaviour of Andalusian political parties, the data indicate that the party that has used Instagram the most (RQ1) is Vox, followed by another new party, Podemos-A. In last place is one of the traditional parties, the PSOE-A. This suggests that new parties (Vox was established in 2013, Podemos in 2014) tend to produce more images than traditional parties, which stands in contrast to evidence of greater Instagram activity by traditional party leaders in the 2016 election (Marcos García & Alonso Muñoz, 2017). Our results are in line with Turnbull-Dugarte (2019), who showed that new parties posted more Instagram content in 2015 and 2016 elections than traditional ones. However, the PP-A has posted more often than then-emerging party Ciudadanos-A. Thus, in light of these results, it seems that novelty is not necessarily a determining factor when it comes to Instagram activity. Nor is ideology a determining factor, which contradicts research by Antonio Pineda et al., (2022, p. 1151), since Vox and Podemos-A are the most active parties on Instagram, and both are at opposite ends of the spectrum. Specifically, data on Vox coincide with previous research highlighting the active use and impact of this ultra-conservative party on SNSs (Aladro Vico & Requeijo Rey, 2020; Castro Martínez & Díaz Morilla, 2021; Cea Esteruelas, 2019).

Regarding RQ2, it is clear that authentic dialogue with citizens through Instagram remains at 0% in all parties. Hence, it could be said that robust interaction is non-existent in Andalusian online politics. This finding places our study in line with previous research confirming the scant use made by politicians in taking advantage of Instagram to interact with their audience (Pineda et al., 2022; Russmann & Svensson, 2017; Verón Lassa & Pallarés Navarro, 2017). However, by focusing on mechanisms for inviting and approaching dialogue (López-Rabadán & Mellado, 2019), the results are slightly more nuanced. Mechanisms of invitation to dialogue—such as mentions, which imply an intermediate level of interactivity—indicate that the PP-A is the party that receives most likes on its publications, and the parties with the highest average number of comments are the two traditional forces, PSOE-A and PP-A. These results contrast with Turnbull-Dugarte’s study (2019), who found that new parties Podemos and Ciudadanos had the most Instagram engagement during the 2015 and 2016 elections. Along the same lines, research by Gonzálvez Vallés et al., (2021) found that Vox and Unidas Podemos were the parties that generated the most interaction on Instagram in the 2019 Spanish general elections. Nevertheless, our results are partially in agreement with María-Teresa Gordillo-Rodríguez and Elena Bellido-Pérez (2021), who state that in the April 2019 election, the PP was the party with the second highest level of engagement, with Vox being the first. Pertaining to mentions, three new parties stand out: Vox, Podemos-A, and Ciudadanos-A, which are also the only ones that have more publications with mentions than without—curiously, in a 2017 study on the region of Catalonia carried out by Cartes Barroso (2018), Ciudadanos used this resource the least on Instagram, whereas Podemos did not use it whatsoever. Consequently, and in response to RQ3, the results seem to be divided in terms of the use of mechanisms for inviting dialogue: on the one hand, traditional Andalusian parties stand out in likes and comments; on the other, new parties are strong regarding mentions. Thus, interactive resources seem to be used differently by the same party in different regions.

As to approaching-dialogue mechanisms, which imply the lowest level of interactivity, right-wing forces Vox-A and PP-A―actually, the furthest to the right of the Andalusian political range—stand out in the number of hashtags they use, hence indicating that the use of some digital resources may be ideology-related. Again, this finding contrasts with Cartes Barroso’s study (2018), in which Podemos was the party using hashtags more often, yet at the same time it is partially in line with Pineda et al., (2022), who found robust use of the tool by the leader of the PP. The use of links was not relevant, except in the case of Podemos-A, although the only parties to use them (at least one time) belong to the left wing of the spectrum. Thus, the response to RQ4 is divided again, although on this occasion the division is grounded on ideology: the right excels in its use of hashtags, whereas the left stands out—albeit very slightly—in the instrumentalisation of links. In any case, and in light of the responses to RQ3 and RQ4, the party that appears to show the greatest interest in making an interactive use of Instagram through secondary indicators is radical national-populist Vox, although the conservative PP-A and the leftist Podemos-A are also noteworthy in this task.

The present discussion has deeper theoretical implications. The use of secondary indicators of interactivity is closer to media rather than human interaction (Stromer-Galley, 2000), since these mechanisms allow the receiver to control the message (Lilleker, 2015). Andalusian parties use Instagram as just another mass communication channel, without taking advantage of the medium’s potential for dialogue—in fact, not even smaller parties, with less visibility in traditional media, express an interactive attitude toward their public by taking advantage of Instagram. Thus, offline political communication trends continue to happen in the online world. As concluded by Tamara A. Small and Thierry Giasson (2020), this may be due to the fear experienced by parties in losing control of their message; however, our study covers a fairly extensive time frame when there was no electoral period, nor well-defined rhythms, hence the ultimate reasons behind the lack of interactivity must go beyond the need of controlling electoral messaging. As such, this lack of dialogue for an entire year defined by a global pandemic may be even more striking, since Instagram was not politically used in a robust interactive way during the devastating health crisis. Consequently, our hypothesis is confirmed: Andalusian parties do not make a truly interactive use of Instagram, or at least an interactive use involving real dialogue. This happens in spite of the fact that several empirical studies show that interactivity positively influences the image that users have of the political class, and is one of their motivations for using SNSs (Castells, 2009; López Abellán, 2012; Painter, 2015; Sundar et al., 2003). In a context where Instagram use in Andalusia would seem to be closer to a mass media logic than to an interaction-oriented, network media logic (Klinger & Svensson, 2015), political communication practitioners fail to take advantage of tools and strategies that could be beneficial to them.

Regarding RQ5—focused on the most popular topics on Instagram—Vox, Podemos-A, Adelante Andalucía, Ciudadanos-A, and IU-A coincide in “Economy and Business”, with “Government” being a secondary topic that coincides with the Vox, IU-A and PSOE-A profiles, which address economic and governmental themes that have great prominence, according to previous research on the use of Instagram in Spain (Pineda et al., 2022). Moreover, these results can also be read in light of the issues expressed by Andalusian voters as being the most important problem (CEA, 2019, 2020), since voters’ expressed concern about unemployment correlates with the systematic use of economy and business as the main topic on Instagram—besides, in late 2020 concern about unemployment was even higher, followed by the COVID problem (as an health and economic issue). This comparison also indicates that, in certain cases, digital strategies and voter concerns are unrelated: although Socialist voters were the most worried about unemployment in late 2019 and late 2020, the PSOE-A only addressed the economy in 7.9% of its 2020 posts.

With regard to the purposes of the posts (RQ6), “Taking a party’s position / posture” stands out as the main objective of the posts of all parties, with the exception of PSOE-A. This contrasts with Turnbull-Dugarte’s findings (2019) about the Spanish context, according to which Instagram is not generally used as a medium to systematically communicate political positions. Thus, it can be concluded that Instagram use in Andalusian politics—that is, in a regional-level context—has its own characteristics and would imply a communication model that does not necessarily fit national-level models.

To sum up, our findings regarding the use of interactive SNS options seem to contradict the predisposition toward participatory politics at a time when more and more initiatives are emerging from public administrations, academic institutions, and civil society seeking to promote open government. In the case of Andalusia, the Ley de Participación Ciudadana de Andalucía (Ley 7/2017, de 27 de diciembre—Andalusian Law of Citizen Participation, Law 7/2017, December, 27—) can be cited, and projects such as the Andalusian Observatory of Citizen Participation, the Chair of Citizen Participation from the University of Córdoba, and Laboratory 717 for Participation and Democratic Innovation of Andalusia (Pérez Gómez & Mahou Lago, 2020) have appeared in recent years. In this context, ICTs in general, and social media in particular, could foster the path towards a truly participatory democracy.

This study has attempted to shed light on the scope and limits of the interactive political use of Instagram, but it has limitations. One of these constraints is the regional context of the data. Thus, we should be careful about generalising the findings to other political levels. Another limitation relates to the results, which reflect the communication of Spanish organizations, hence they might not represent that of their regional peers in other countries—as asserted by Enli and Moe, “The impact of social media on election campaigns is fairly diverse across different regions and countries, depending on media environments, cultural practices, and political systems” (2013, p. 641). Moreover, new lines of research are opened, such as the analysis of Instagram interactive communication in diverse political contexts, as well as the degree with which Andalusian parties receive likes and comments, hence shedding light on citizen/voter engagement.

7 Acknowledgment

This paper originates in the research project proposal PRY095/19, funded by Fundación Pública Andaluza Centro de Estudios Andaluces (11th edition). The research project title is “Communication, Participation, and Dialogue with the Citizenry in the “New Politics” Age: The Use of Social Media by Andalusian Political Parties”.

8 References

Adelante Andalucía [@adelanteandalucia]. (August 14, 2020). #AndalucíaNoTieneRey. [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CD3Z1jMKWCN/?igsh=YTNhcTM2NThiM3o%3D

Ahmed, Saifuddin & Skoric, Marko M. (2014). My name is Khan: the use of Twitter in the campaign for 2013 Pakistan General Election. In Ralph H. Sprague Jr. (Ed.), Proceedings of the Forty-Seventh Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 2242-2251). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2014.282

AIMC (2019). Navegantes en la Red- Encuesta AIMC a usuarios de Internet. Report no. 21, October-December. Autor.

Aladro Vico, Eva & Requeijo Rey, Paula (2020). Discurso, estrategias e interacciones de Vox en su cuenta oficial de Instagram en las elecciones del 28-A. Derecha radical y redes sociales. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 77, 203-229. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2020-1455

Bast, Jennifer (2021). Managing the Image. The Visual Communication Strategy of European Right-Wing Populist Politicians on Instagram. Journal of Political Marketing, 23(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2021.1892901

Bellido-Pérez, Elena & Gordillo Rodríguez, María-Teresa (2022). Elementos para la construcción del escenario del candidato político en Instagram. El caso de las elecciones generales del 28 de abril de 2019 en España. Estudios sobre el mensaje periodístico, 28(1), 25-40. https://doi.org/10.5209/esmp.75870

Bekafigo, Marija A. & McBride, Allan (2013). Who Tweets About Politics? Political Participation of Twitter Users During the 2011 Gubernatorial Elections. Social Science Computer Review, 31(5), 625-643. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439313490405

Consejo Audiovisual de Andalucia [CAA] (2020). Barómetro audiovisual de Andalucía 2020. Report. https://consejoaudiovisualdeandalucia.es/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/barometro_2020-digital.pdf

Cartes Barroso, Manuel Jesús (2018). El uso de Instagram por los partidos políticos catalanes durante el referéndum del 1-O. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 47, 17-36. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2018.0.17-36

Castells, Manuel (2009). Communication Power. Oxford University Press.

Castro Martínez, Andrea & Díaz Morilla, Pablo (2021). La comunicación política de la derecha radical en redes sociales. De Instagram a TikTok y Gab, la estrategia digital de Vox. Dígitos, 7, 67-89.

Cea Esteruelas, María Nereida (2019). Nivel de interacción de la comunicación de los partidos políticos españoles en redes sociales. Marco: revista de márketing y comunicación política, 5, 41-57.

Cebrián Guinovart, Elena; Vázquez Barrio, Tamara & Olabarrieta Vallejo, Ane (2013). ¿Participación y democracia en los medios sociales?: El caso de Twitter en las elecciones vascas de 2012. adComunica, 6, 39-63. https://doi.org/10.6035/2174-0992.2013.6.4

Centro de Estudios Andaluces [CEA] (2019). Barómetro Andaluz. Estudio de Opinión Pública de Andalucía. Diciembre 2019. Autor. https://www.centrodeestudiosandaluces.es/barometro/barometro-andaluz-de-diciembre-2019

Centro de Estudios Andaluces [CEA] (2020). Barómetro Andaluz. Estudio de Opinión Pública de Andalucía. Diciembre 2020. Autor. https://www.centrodeestudiosandaluces.es/barometro/barometro-andaluz-de-diciembre-2020

Criado, J. Ignacio; Martínez-Fuentes, Guadalupe & Silván, Aitor (2013). Twitter en España: las elecciones municipales españolas de 2011. RIPS, 12(1), 93-113.

Ekman, Mattias & Widholm, Andreas (2017). Political communication in an age of visual connectivity: Exploring Instagram practices among Swedish politicians. Northern Lights, 15(1), 15-32. https://doi.org/10.1386/nl.15.1.15_1

Enli, Gunn Sara & Moe, Hallvard (2013) Introduction to Special Issue. Information, Communication & Society, 16(5), 637-645. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.784795

Enli, Gunn Sara & Skogerbø, Eli (2013). Personalized campaigns in party-centered politics: Twitter and Facebook as arenas for political communication. Information, Communication and Society, 16(5), 757-774. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.782330

Ferber, Paul; Foltz, Frank & Pugliese, Rudy (2007). Cyberdemocracy and Online Politics: A New Model of Interactivity. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 27(5), 391-400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467607304559

Filimonov, Kirill; Russmann, Uta & Svensson, Jakob (2016). Picturing the Party: Instagram and Party Campaigning in the 2014 Swedish Elections. Social Media + Society, 2(3), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116662179

García Orta, María José (2011). A la caza del voto joven: el uso de las redes sociales en las nuevas campañas 2.0. Sociedad Española de Periodística. XVII Congreso Internacional “Periodismo político: nuevos retos, nuevas prácticas” (pp. 79-93). Universidad de Valladolid.

García Ortega, Carmela & Zugasti Azagra, Ricardo (2014). La campaña virtual en Twitter: análisis de las cuentas de Rajoy y de Rubalcaba en las elecciones generales de 2011. Historia y Comunicación Social, 19, 299-311. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_HICS.2014.v19.45029

Gonzálvez Vallés, Juan Enrique; Barrientos-Báez, Almudena & Caldevilla-Domínguez, David (2021). Gestión de las redes sociales en las campañas electorales en 2019. Anàlisi, 65, 67-86. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/analisi.3347

Gordillo Rodríguez, María-Teresa & Bellido-Pérez, Elena (2021). Politicians self-representation on Instagram: the professional and the humanized candidate during 2019 Spanish elections. Observatorio (OBS*), 15(1), 109-136. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS15120211692

Graham, Todd; Broersma, Marcel; Hazelhoff, Karin & Van’t Haar, Guido (2013). Between broadcasting political messages and interacting with voters. The use of Twitter during the 2010 UK general election campaign. Information, Communication & Society, 16(5), 692-716. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.785581

Grusell, Marie & Nord, Lars (2020) Not so Intimate Instagram: Images of Swedish Political Party Leaders in the 2018 National Election Campaign. Journal of Political Marketing, 22(2), 92-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2020.1841709

Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE] (2020). Cifras oficiales de población resultante de la revisión del Padrón municipal. https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177011&menu=resultados&idp=1254734710990

Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE] (2022). Encuesta sobre equipamiento y uso de tecnologías de información y comunicación en los hogares 2022. https://www.ine.es/dynt3/inebase/index.htm?padre=8921&capsel=8923

Klinger, Ulrike & Svensson, Jakob (2015). The emergence of network media logic in political communication: A theoretical approach. New Media & Society, 17(8), 1241-1257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814522952

Krippendorff, Klaus (2004). Content Analysis. Sage.

Lalancette, Mireille & Raynauld, Vincent (2017). The Power of Political Image: Justin Trudeau, Instagram, and Celebrity Politics. American Behavioral Scientist, 63(7), 888-924. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764217744838

Lilleker, Darren G. (2015). Interactivity and branding: Public political communication as a marketing tool. Journal of Political Marketing, 14(1-2), 111-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2014.990841

Lilleker, Darren G. (2016). Comparing online campaigning: The evolution of interactive campaigning from Royal to Obama to Hollande. French Politics, 14(2), 234-253. https://doi.org/10.1057/fp.2016.5

Loader, Brian D. & Mercea, Dan (2011). Introduction. Networking democracy? Social media innovations and participatory politics. Information, Communication & Society, 14(6), 757-769. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783956506765-7

López Abellán, Mónica (2012). Twitter como instrumento de comunicación política en campaña: Elecciones Generales 2011. Cuadernos de Gestión de Información, 2, 69-84.

López-Rabadán, Pablo & Doménech-Fabregat, Hugo (2018). Instagram y la espectacularización de las crisis políticas. Las 5W de la imagen digital en el proceso independentista de Cataluña. El profesional de la información, 27(5), 1013-1029. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.sep.06

López-Rabadán, Pablo & Mellado, Claudia (2019). Twitter as space for interaction in political journalism. Dynamics, consequences and proposal of interactivity scale for social media. Communication & Society, 32(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.32.37810

Marcos García, Silvia & Alonso Muñoz, Laura (2017). La gestión de la imagen en campaña electoral. El uso de Instagram por parte de los partidos y líderes españoles en el 26J. In Javier Sierra-Sánchez & Sheila Liberal-Ormaechea (Eds.), Uso y aplicación de las redes sociales en el mundo audiovisual y publicitario (pp. 107-118). McGraw-Hill.

McMillan, Sally J. (2002a). A four-part model of cyber-interactivity: Some cyber-places are more interactive than others. New Media & Society, 4(2), 271-291. https://doi.org/10.1177/146144480200400208

McMillan, Sally J. (2002b). Exploring models of interactivity from multiple research traditions: Users, documents, and systems. In Leah A. Lievrouw & Sonia Livingstone (Eds.), Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Consequences of ICTs (pp. 163-182). Sage.

Muñoz, Caroline Lego & Towner, Terri L. (2017). The Image is the Message: Instagram Marketing and the 2016 Presidential Primary Season. Journal of Political Marketing, 16(3-4), 290-318. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2017.1334254

Painter, David Lynn (2015). Online political public relations and trust: Source and interactivity effects in the 2012 US presidential campaign. Public relations review, 41(5), 801-808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.06.012

Parmelee, John & Roman, Nataliya (2020). The strength of no-tie relationships: Political leaders’ Instagram posts and their followers’ actions and views. First Monday, 25(9). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v25i9.10886

Peng, Yilang (2021). What Makes Politicians’ Instagram Posts Popular? Analyzing Social Media Strategies of Candidates and Office Holders with Computer Vision. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(1), 143-166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220964769

Pérez Gómez, Domingo Jesús & Mahou Lago, Xosé María (2020). Participación ciudadana online. Una aproximación a los mecanismos de participación en Andalucía. Fundación Pública Andaluza Centro de Estudios Andaluces.

Pineda, Antonio; Bellido-Pérez, Elena & Barragán-Romero, Ana-Isabel (2022). “Backstage moments during the campaign”: The interactive use of Instagram by Spanish political leaders. New Media & Society, 24(5). 1133-1160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820972390

Pineda, Antonio; Fernández Gómez, Jorge David & Rebollo-Bueno, Sara (2021). “We Have Taken a Major Step Forward Today”: The Use of Twitter by Spanish Minor Parties. Southern Communication Journal, 86(2), 146-164. https://doi.org/10.1080/1041794X.2021.1882545

Powell, Larry & Cowart, Joseph (2003). Political Campaign Communication. Allyn and Bacon.

PP de Andalucía [@ppandalucia]. (October 29, 2020). Andalucía anticipándose está preparada para hacer frente a la tercera ola. Se ha almacenado […] [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CG7U0eAp-dw/?igsh=MXM0NXcwd3FocDd2

Quevedo-Redondo, Raquel & Portalés-Oliva, Marta (2017). Imagen y comunicación política en Instagram. Celebrificación de los candidatos a la presidencia del Gobierno. El profesional de la información, 26(5), 916-927. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.13

Ramos-Serrano, Marina; Fernández Gómez, Jorge David & Pineda, Antonio (2018). ‘Follow the closing of the campaign on streaming’: The use of Twitter by Spanish political parties during the 2014 European elections. New Media & Society, 20, 122-140. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816660730

Ruiz del Olmo, Francisco Javier & Bustos Díaz, Javier (2016). Del tweet a la fotografía, la evolución de la comunicación política en Twitter hacia la imagen. El caso del debate de estado de la nación en España (2015). Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 71, 108-123. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2016-1086

Russmann, Uta & Svensson, Jakob (2017). Interaction on Instagram? Glimpses from the 2014 Swedish Elections. International Journal of E-Politics, 8(1), 50-66. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJEP.2017010104

Selva-Ruiz, David & Caro-Castaño, Lucía (2017). Uso de Instagram como medio de comunicación política por parte de los diputados españoles: la estrategia de humanización en la “vieja” y la “nueva” política. El profesional de la información, 26(5), 903-915. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.12

Serfaty, Viviane (2012). E-The People: a comparative perspective on the use of social networks in U.S. and French electoral campaigns. Revista Comunicação Midiática, 7(3), 195-214.

Shane-Simpson, Christina; Manago, Adriana; Gaggi, Naomi & Gillespie-Lynch, Kristen (2018). Why do college students prefer Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram? Site affordances, tensions between privacy and self-expression, and implications for social capital. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 276-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.041

Small, Tamara A. (2011). What the hashtag? A content analysis of Canadian politics on Twitter. Information, Communication & Society, 14(6), 872-895. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.554572

Small, Tamara A. & Giasson, Thierry (2020). Political Parties: Political Communication in the Digital Age. In Tamara A. Small & Harold Jansen (Eds.), Digital Politics in Canada (pp. 136-158). University of Toronto Press.

Stromer-Galley, Jennifer (2000). On-Line Interaction and Why Candidates Avoid It. Journal of Communication, 50(4), 111-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02865.x

Sundar, S. Shyam; Kalyanaraman, Sriram & Brown, Justin (2003). Explicating web site interactivity: Impression formation effects in political campaign sites. Communication research, 30(1), 30-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650202239025

The Social Media Family (2020). IV Estudio sobre los usuarios de Facebook, Twitter e Instagram en España. https://www.amic.media/media/files/file_352_2282.pdf

The Social Media Family (2022). Estadísticas de uso de Instagram (y también en España) [2022]. https://thesocialmediafamily.com/estadisticas-uso-instagram/#ESTADISTICAS_MUNDIALES_DE_USO_DE_INSTAGRAM

Turnbull-Dugarte, Stuart J. (2019). Selfies, Policies, or Votes? Political Party Use of Instagram in the 2015 and 2016 Spanish General Elections. Social Media + Society, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119826129

Vergeer, Maurice & Hermans, Liesbeth (2013). Campaigning on Twitter: Microblogging and Online Social Networking as Campaign Tools in the 2010 General Elections in the Netherlands. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18, 399-419. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12023

Vergeer, Maurice; Hermans, Liesbeth & Sams, Steven (2011). Online social networks and micro-blogging in political campaigning: The exploration of a new campaign tool and a new campaign style. Party Politics, 19(3), 477-501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068811407580

Verón Lassa, José Juan & Pallarés Navarro, Sandra (2017). La imagen del político como estrategia electoral: el caso de Albert Rivera en Instagram. Mediatika, 16, 195-217.

VOX Parlamento de Andalucía [@andalucia_vox]. (November 11, 2020). Ante la alarma social por la posible venta de género no esencial en grandes superficies fuera de horario o poblaciones con cierre total […]. [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/tv/CHdKaEBqLnH/?igsh=MWg5ZmJvdnBoemU4cg%3D%3D

Zugasti Azagra, Ricardo & Pérez González, Javier (2015). La interacción política en Twitter: el caso de @ppopular y @ahorapodemos durante la campaña para las Elecciones Europeas de 2014. Ámbitos, 28. https://doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.2015.i28.07