Organizaciones de Salud Pública: ¿Liderazgo o Gestión?

Public Healthcare Organizations: Leadership or Management?

- Maite Martínez-Gonzalez

- Pilar Monreal-Bosch

- Santiago Perera

- Clara Selva Olid

- Palabras clave:

- Sanidad

- Liderazgo

- Gestión Sanitaria

- Cuestionario (MLQ-5X)

- Keywords:

- Healthcare

- Leadership

- Management

- Questionnaire (MLQ-5X)

1 Introduction

In Catalonia, healthcare centers and health resources form part of the Catalan Health Service (CHS), the organism which oversees the provision of healthcare services. To ensure that these health services reach all the population effectively and with quality, the CHS has a network of centers throughout the Catalan territory which constitute the integral public health system (SISCAT): primary care centers, local clinics, hospitals, health and social care centers and mental health institutions, which functions are the health promotion and (or) education of the population (No. 5776, 2010). The hospitals and centers are distributed according to the distribution pattern of the population. Medical and healthcare management is responsible for managing these centers and hospitals and currently comprises a highly capable group of well-trained and experienced professionals with a strong will and a strong sense of public service vocation (Mauri, 2009). Healthcare organizations, like other organizations, are undergoing reform to become more customer-oriented, to reduce product manufacturing times, to streamline work processes, to simplify hierarchies and to introduce new methods of coordination, control and information flow networks (Gutierrez, Ferrús & Craywinckel, 2009).

Until the mid-1990s, the CHS was very centralized and required health managers to focus on short term objectives and work with a management style characterized by negotiation and authority. In recent decades, management has acquired a more global view, obtaining greater recognition within the healthcare system and providing greater empowerment of healthcare professionals. The healthcare system is complex one, requiring a manager-leader who can link the world of management to the world of frontline healthcare; someone with an understanding of the needs of the diverse demands of its service users and how the service can meet those needs (Jaskyte, 2003; Menarguez & Saturno, 1998). Consequently, a new type of leadership is required (Del Llano, Martínez-Cantarero, Gol & Raigada, 2002), one where the professional responsible for a team or project is able to develop policies that promote, manage and lead.

Healthcare organizations must strive to maintain service quality and improve efficiency in order to improve service user satisfaction, all the while adhering to the restrictions placed on them by the public service budgets. Management, leadership and change in management style are currently the three strategic priorities of healthcare centers. In this article we focus on leadership as a process of social influence, i.e. “The essence of leadership in organizations is influencing and facilitating individual and collective efforts to accomplish shared objectives” (Yukl, 2012, p. 66).

Leadership has been one of the most frequently studied concepts in behavioral science (e.g. Transformational leadership [Bass, 1998; 1999], Leader-Member Exchange Theory (LMX) [Dansereau, Graen & Haga, 1975], or Shared leadership [Pearce & Con

ger, 2003]). However, few studies focus on addressing leadership in the Spanish healthcare arena and even fewer using a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods (March, Prieto, Hernán & Solas, 1999). Recent mixed methods studies and models have tended to focus on the transformation of individuals, groups and organizations (Nielsen, Raudall, Yarker & Brenner, 2008). The Bass and Avolio model (1995/2004) is one example of an organizational transformation model. Bernard Bass and Bruce Avolio stressed that transformational leadership is a process of influence, by which leaders change how employees think about what is important, and help them to see themselves, and the opportunities and challenges of their environment, in a new way.

Transformational leadership, according to these authors, results in performances which exceed expectations. One might say that the transformational leader successfully addresses conflict or stress, and enables employees to tolerate uncertainties by giving them a measure of security, thus it is these characteristics which make transformational leadership particularly useful in times of organizational change (Bass & Bass, 1974/2008; Pierro, Raven, Amato & Bélanger, 2013).

Bass and Avolio (1995/2004) argued that transactional leadership occurs when people initiate contact with each other in order to exchange things of value, i.e. transactional leadership defines expectations and promotes a mechanism for achieving high performance levels. Transactional leaders exhibit behaviors associated with constructive and corrective transactions: they clarify what is required to achieve results, they detect irregularities and failures and the actions they choose to take may be preventive or palliative.

Transactional leadership is characterized by the recognition of contingencies along with the active or passive management of any exceptional situations. One might say that transactional leadership is especially useful in stable contexts, where the focus is on remedial interventions with specific objectives.

1.1 Objective

In the situation currently facing the CHS managers, both in hospitals and primary care providers, how to be efficient and effective leaders is paramount. Starting from this premise, the main objective of this article is then to explore the current leadership in the CHS. More specifically, we analyze which leadership styles (according to the Bass and Avolio model, 1995/2004) which are being used in the different healthcare centers around Catalonia.

2 Method

2.1 PHASE 1

2.1.1 Participants and Procedure

The sample is composed of 120 top level managers from different healthcare centers; namely 27 hospitals (42% of hospitals in Catalonia), 25 primary care units, which represent the different health regions that the Catalan area is divided into, and 17 headquarters. Fifty-nine of the 120 participants were women. Depending on the position the managers held, they were involved in one or both of the two general activities idetified. Specifically, 64 of them were only involved in management, while 56 of them were involved in both management and support.

The 120 repsondents were given a questionanaire designed so they could evaluate exclusively their own management style. At the end of 2013, data collection sessions were held with groups of participants who filled out individual questionnaires. (It took approximately 12 minutes for the questionnaires to be completed). In each session researchers explained the objective of the research and were available to answer any questions that the employees may have had.

2.2 PHASE 2

2.2.1 Participants and Procedure

Critical incident interviews (Flanagan, 1954) were held with 14 managers from several healthcare centers (five nurses and nine doctors) in order to explore the managers’ key competencies. Participation was voluntary and took place during working hours. (NB: approximately 60 minutes was required per interview). All interviews were audio-recorded and anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed. Data were collected at the beginning of 2014.

2.3 Measures

Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X). The scale contained 36 items in total. A 5-point Likert response scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always) was used. Items covered the four dimensions proposed by Molero, Recio & Cuadrado (2010), who validated the present questionnaire in a Spanish sample. Sample items assessing leadership included such questions as: to what extent do I (1) create an optimistic and motivational vision of the future, (2) suggest to my staff new ways of coping with tasks, (3) help my staff enhance their strengths, or (4) act only when absolutely necessary? Internal consistency reliability for the scale was 0.81.

Critical Incident Interviews (CII). The interviews contained different questions oriented towards detecting the different competencies managers need to do their job effectively in that particular setting. In order to do that, a Critical Incident Technique was used in which managers had to respond about what happened, where and why in regards to a problematic situation or an issue which had risen during the day-to-day activities of their job. Sample questions from CII included (1) describe a relevant problematic or unexpected event that has occurred in your job in recent months, and (2) describe a crucial task you have to deal with in your position (Berger, Yepes, Gómez-Benito Quijano & Brodbeck, 2011).

Analysis

To explore the differences in leadership, (based on either the type of healthcare center or the type of activity the board of managers were involved in), in Phase 1 a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for each leadership factor using SPSS 19.0.

In Phase 2, (in order to understand in the participants’ own words what leadership is like in the Catalan Health System), this analysis was based on three consecutive steps (a) discovery, (b) analysis , and (c) relativization. To ensure the reliability of the process, the research team triangulated the allocation of categories. Quotations were selected to illustrate the categorization.

3 Results

3.1 PHASE 1

M = 3.20, SD = .39) and transformational leadership (M = 3.15, SD = .37) highly, whereas passive leadership (M = 2.78,

SD = .36) and corrective leadership (M = 2.27, SD = .73) received medium scores. Pearson correlations revealed positive relationships among all the variables (p < .01) (see Table 1).

| Leadership factor | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Develop./Transactional | 3.20 | .39 | - | ||||

| 2. Transformational | 3.15 | .37 | .667** | - | |||

| 3. Pasive | 2.78 | .36 | .273** | .150 | - | ||

| 4. Corrective | 2.27 | .73 | .097 | .132 | 0.60 | - |

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations between Leadership Factors

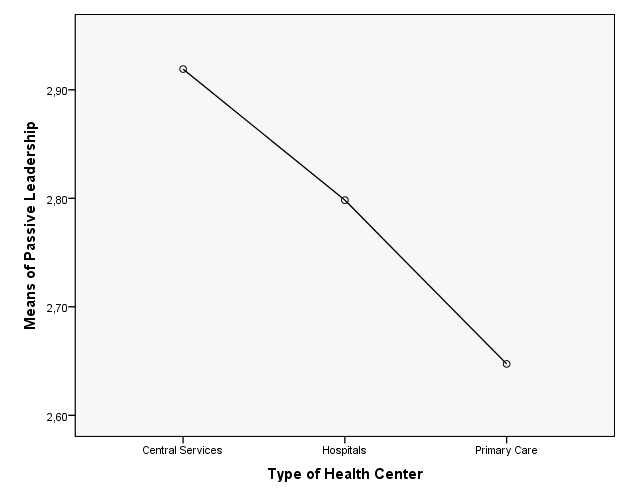

On the one hand, one-way ANOVA showed significant differences in passive leadership for each type of healthcare center (F (2.119) = 3.35, p < .05 (see Fig. 1). However, no significant differences for the other leadership styles were detected and in all the centers management approaches were found to be very similar. Headquarters had a significantly higher mean in passive leadership style than hospitals and primary healthcare services.

Figura 1

Intercorrelations between Passive Leadership and Type of Health Center

Next, a qualitative study was carried out to expand on the quantitative results obtained. A content analysis, using a bottom-up strategy, enabled first-order and second-order categories to be generated using either the raw data or the interview data (see Annex).

4 Discussion

The quantitative results show medium to high scores in four leadership factors, with transactional leadership and transformational leadership (means above 3) taking a prominent role. The high significant correlation between the factors of transactional and transformational leadership that emerged from the results, is noteworthy as it defines these two leadership styles as being predominant in our sample and indicates, as has been found in other investigations (Bass & Bass, 1974/2008), that they are strongly related.

The analysis of differences between leadership style and type of center revealed significant differences, although this may in fact indicate that with the MLQ-5X data we do not have enough information to account for which leadership styles are being used in the various Catalan healthcare system centers. Only passive leadership presents differences among the centers and it is precisely this kind of leadership which has a significant correlation with transactional leadership. The significance of these differences can be found in the delegation processes of decision-making, and is one that has been established by the organization itself, i.e. decision-making that is more focused on the team of professionals has significantly lower passive leadership scores (e.g. hospitals) than that of the diluted decision-making found in a central services organization.

By analyzing qualitative data we are able to describe and understand exactly what leadership styles are present in these healthcare centers as well as the relationships between the styles. In this context, the qualitative results show transformational and transactional leadership behaviors which characterize the subjects of our study: managers of public healthcare centers in Catalonia. Both styles are perfectly compatible and even complimentary in the reality of the healthcare scenario (Avolio & Bass, 1995/2004). In this context, there seems to be agreement between researchers that in dynamic and changing contexts, transformational leadership may well result in being the most efficient style of management (Bass, 1999). The transformational leader is depicted as someone who should be able to access and manage various information sources, transform the information to make it adequate for the reality at hand, and transfer the information to their team, making it understandable and motivating so that it leads to positive action.

Managers on a macro level need to be very well informed about the center’s health context and work agenda, thus “communication competence” becomes especially relevant when exercising transformational leadership. This feature, described by the study’s subjects, differentiates the efficacy of truly ‘transformational’ leaders in terms of information from those known as ‘passive informants,’ i.e. a more committed action of persuasion can be discerned, rather than merely a simple transmission of objectives (which can lead to thinking that simple information is sufficient to motivate or change behaviors) (Hanson & Ford, 2010). This is why some authors (Berger et al., 2011) point out (in terms of leading teams) the need to “reflect” on why things are done in one way or another.

Decision-making is not a characteristic element of mangers and this would explain the scores obtained in the questionnaire. In other words, these managers only assume the more global or strategic decisions and delegate the more operative decisions and practices to their healthcare professionals. This would explain why passive leadership is present in this study, i.e. it is a form of transaction with staff or easing of their tasks as manager, as they have staff who are highly competent professionals and more than capable of making day-to-day decisions. In this context, we consider the self-reporting questionnaire on the leadership style used as not being sufficiently sensitive to be able to capture this form of management in healthcare. It may appear to an outsider that the leader, either by not deciding or by being a passive leader, does not have full control over the situation, but in reality, this way of doing things encompasses three motivating actions: co-worker recognition, openness and participation.

The transactional leadership described in this article, forces the manager to be very focused on planning, achieving goals within deadlines, managing and facilitating the resources required to achieve the objectives and (when needed) “intervening and/or correcting” the teams, so that they can achieve their goals. Taking into account the current situation of a serious economic crisis in the healthcare sector at large, being efficient in given strategic goals has acquired a crucial importance (Berger, Romeo, Guardia, Yepes & Soria, 2012). In this context, the qualitative results allow us to describe the current leadership in the CHS and lead us to ponder whether this is truly leadership or if we are talking about simple management of these entities.

We have drawn two conclusions from the study conducted. Firstly, the health system, as it is currently structured, makes it difficult to speak clearly of leadership. Strategically the concern is in finding efficient solutions to the social, political and economic reality, and seeks to provide service quality, although not always in the strictest terms of norms and functioning protocols. This leads staff to assume that the management team of a center should oversee, within the framework of certain determined parameters, the professional staff that make up the organization and the work they do.

However, despite this perception, in this context the professional with management duties is in fact equiped with the basic tool required to go from a manger of information to a transformative leader, i.e. “communication competence”. This competence allows managers to value, reflect, contextualize and transform the current reality into a future project shared by their professional teams. What has been proven is, that in reality the difficult and stagnating situation experienced by many centers can be modified in a proactive way. Thus, we firmly believe that the competence of communication should characterize the contemporary leader.

Finally, we would like to mention the questionnaire used. Despite having been proven as reliable and viable in various contexts, we feel that is not sufficiently sensitive to address the reality of health organization managers in the Catalan healthcare system as it prevents the subject from identifying with some behaviors presented by the questionnaire. Consequently, the description of the behaviors, as outlined in the interviews, has been a key element in complementing the study of leadership in the Catalan healthcare system.

The most relevant limitation of this study is precisely one of its strengths, the composition of the sample. Despite the fact that it is not very broad, we have to consider that this is composed for management positions that represent the entire Catalan healthcare organization and its various centers.

5 Annex: Analytical process followed

| First-order categories | Second-order categories | Quotations* |

|---|---|---|

| Transformational Leadership | Find alternatives using available information | I search for information anywhere I might find it. I almost always look for additional information or I look for other ways to do the things (Interviewed 1, personal interview, February, 2014) |

| Complete the information | I interact informally with those who have the same management level as me and with the information I gain from talking with them I know what they are doing in other areas ... (Interview 1, personal interview, February, 2014) | |

| Transmit information | An important task is the transmission and interpretation of all actions that are centralized in the institution itself. (Interview 11, personal interview, March, 2014) | |

| Find different alternatives to solve problems | We talk to different centers and different people and seek ways to solve problems. (Interview 5, personal interview, March, 2014) | |

| Talk about goals and targets to be achieved | We always try, as far as possible, to meet the objectives and goals that each professional group must reach. (Interview 2, personal interview, February, 2014) | |

| Specify the importance of reaching goals | There are a number of tasks that involve strategic management: transmitting what the lines of work are, the strategic objectives or the objectives of specific teams. (Interview 7, personal interview, January 2014). | |

| Make sense of what is or should be | What I am trying to do is to make them to see what is inside a company, that they are not an island, and if the entire company decides on one specific line, this is because studies have been carried out that show this is the best line of action to take. (Interview 2, personal interview, February, 2014) | |

| Contextualize objectives | Earlier this year, we outlined the center's objectives to the professionals, explaining not only the existing targets, as required by CatSalut, but also the objectives you have to meet every year in each center. (Interview 4, personal interview, March, 2014) | |

| Facilitative Leadership | Provide proven help | All the information has to be corroborated because if I give my assistants any information that I have not corroborated, this could mislead them, and this still involves taking risks on a constant basis. (Interviewed 1, personal interview, February, 2014) |

| Help/Be a mentor | I am the first to get to work… if I'm dynamic, the first person I help is me... this is precisely what leading by example entails. (Interview 10, personal interview, April, 2014) | |

| Plan and distribute resources | My job entails planning structures (healthcare), distributing resources ... (Interview 11, personal interview, March, 2014) | |

| Analyze needs and different expectations | That's what is involved in management, seeing who is suitable for what, if you know your team, you see who is more enthusiastic about doing what... (Interview 4, personal interview, March, 2014) | |

| Clarify issues to meet objectives | Usually we sit with professionals and evaluate whether this or that program will achieve the objectives. (Interview 6, personal interview, January, 2014) | |

| Consider the different needs of each group | Moreover, a primary care manager must be available to these managers to solve their everyday problems. Thus, we all need to have a series of support tools available for them. (Interview 7, personal interview, January, 2014) | |

| Corrective Leadership |

Track errors | I go into the electronic schedules, checking if the schedules are full, or if any patient could still be scheduled, and I check that the professionals who have to do the job will be there. (Interview 10, personal interview, April, 2014) |

| Punish errors | I try to pick up on any errors and negotiate the structural or organizational problems; my last resource would be disciplinary proceedings. (Interview 13, personal interview, January, 2014) | |

| Passive Leadership |

Act only when there are serious problems | The doctor is the one who acts; I only intervene if he asks me. (Interview 14, personal interview, March, 2014) |

| Avoid making decisions | No, each medical manager manages and negotiates. My job is to coordinate processes: I control and evaluate at the end the programs or process. (Interview 6, personal interview, January, 2014) |

* The names of interviewees have been anonymized to preserve their identity

6 Referencias

Avolio, Bruce & Bass, Bernard (1995/2004). Multifactor leadership questionnaire. Manual and sampler set (3rd ed.). Carolina: Mind Garden.

Bass, Bernard (1998). Transformational leadership: Individual, military and educational impact. New York: Psychology Press.

Bass, Bernard (1999). Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8, 9-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/135943299398410

Bass, Bernard & Bass, Ruth (1974/2008). Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Application (4th ed.). Washington DC: Free Press.

Berger, Rita; Romeo, Marina; Guardia, Joan; Yepes, Montserrat & Soria, Miguel Ángel (2012). Psychometric properties of the Spanish Human System Audit Short-Scale of Transformational Leadership. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15, 367-376. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_sjop.2012.v15.n1.37343

Berger, Rita; Yepes, Montserrat; Gómez-Benito, Juana; Quijano, Santiago & Brodbeck, Felix (2011). Validity of the Human System Audit Transformational Leadership Short Scale (HSA-TFL) in four European countries. Universitas Psychologica, 10(3), 657-668.

Dansereau, Fred; Graen, George & Haga, William (1975). A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership in formal organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 13, 46-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(75)90005-7

Decret 5776, de 16 de diciembre de 2010 (DOGC). Extraído de https://www.gencat.cat/eadop/imatges/5776/c5776.pdf

Del Llano, Juan; Martínez-Cantarero, Juan; Gol, Juan & Raigada, Flor (2002). Análisis cualitativo de las innovaciones organizativas en hospitales públicos españoles. Gaceta Sanitaria, 16, 408-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0213-9111(02)71950-x

Flanagan, John (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51, 327-358.

Gutierrez, Ricard; Ferrús, Lena & Craywinckel, Gemma (2009). Les competencies directives en el sistema de Salut de Catalunya. Càtedra de Gestió. Direcció i Administració Sanitàries. Barcelona: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Hanson, William & Ford, Randall (2010). Complexity leadership in healthcare: Leader network awareness. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2, 6587-6596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.04.069

Jaskyte, Kristina (2003). Organizational Culture and Innovation in Nonprofit Human Service Organizations. Dissertation Abstracts International, 63, 23-41. https://doi.org/10.1300/j147v29n02_03

March, Joan Carles; Prieto, Maria Ángeles; Hernán, Mariano & Solas, Olga (1999). Técnicas cualitativas para la investigación en salud pública y gestión de servicios de salud: algo más que otro tipo de técnicas. Gaceta Sanitaria, 13(4), 312-319. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0213-9111(99)71373-7

Mauri, Jordi (2009). Reflexiones sobre la gestión de hospitales en Cataluña desde las transferencias sanitarias. Revista de Administración Sanitaria, 7, 125-130.

Menarguez, Juan Franisco & Saturno, Pedro (1998). Características del liderazgo de los coordinadores de centros de salud en la Comunidad Autónoma de Murcia. Atención Primaria, 22, 636-641.

Molero, Fernando; Recio, Patricia & Cuadrado, Isabel (2010). Liderazgo transformacional y liderazgo transaccional: un análisis de la estructura factorial del Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) en una muestra española. Psicothema, 22(3), 495-501.

Nielsen, Karina; Raudall, Raymond; Yarker, Joanna & Brenner, Sten-Olof (2008). The effects of transformational leadership on followers perceived work chracteristics and psychological well-being: A longitudinal study. Work & Stress, 22, 16-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370801979430

Pearce, Craig & Conger, Jay (2003). All those years ago: The historical underpinnings of shared leadership. In: Pearce, Craig., & Conger, Jay., Shared Leadership: Reframing the Hows and Whys of Leadership (pp. 1-18). Oaks: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452229539.n1

Pierro, Antonio; Raven, Bertran; Amato, Clara & Bélanger, Jocelyn (2013). Bases of social power, leadership styles, and organizational commitment.International Journal of Psychology, 48(6): 1122-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2012.733398

Yukl, Gary (2012). Effective Leadership Behaviors: What We Know and What Questions Need More Attention?. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 26: 66-85. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0088