Authors as Strategic Constructions in the Multimedia Age

Los autores como construcciones estratégicas en la era multimedia

- Andrea Pitasi

What does it mean to be an author as the practices associated with connective and/or collective intelligence continue spreading through the world of the mass-media? More specifically, how are authors, and publishers as well, already undergoing important transformations as new information and communication technologies allow the capitalization of knowledge? The diverse philosophical and sociological implications of this question are explored below in contexts ranging from industrial-organizational knowledge work, to the creation and marketing of popular literary fiction. At both of these extremes, however, the central thesis is “depersonalization.” That is, it will be argued that the effect of the new information/communication systems is to dilute, conceal, or entirely eliminate identification of the single mind or minds that have been absorbed into the systems.

At the industrial-organizational level, for example, new planning and production methods known variously as “knowledge management,” “community of practice,” “lean thinking,” “knowledge sharing,” “E-learning,” etc., essentially operate to first assimilate and then integrate the contributions of different individuals either working in teams or alone in separate corners of the world, into a seamless collective product. And while this model of corporate knowledge production is not new --- it stands as one of the defining characteristics of modernity itself — the sheer mass of information that can be rapidly processed and brought to bear on one or another, or even several objectives simultaneously, is unprecedented. Moreover, this process is often accomplished via the use of automated, “untouched by human hands” algorithms designed to detect and wipe out individual differences or biases. Consequently, with few exceptions, in most organizations individual contributors to the corporate knowledge process can now be more easily and efficiently “squeezed dry” of their intellectual resources than ever before. And it follows that, as may be seen among the large numbers of E-commerce and technology knowledge workers who are presently unemployed, these former low-end information authors have become a surplus commodity in our high tech labor markets. Indeed, their condition might plausibly be seen as comparable that of the exploited 19th century workers so lovingly described by Karl Marx and his disciples. It is no accident that the term “cognitive proletarians” is now becoming a convenient way of referring to various types of low-end authors.

Their status will presently be discussed in greater detail, but another, less obvious transformation is also occurring among high-end authors at the other end of the spectrum. Namely, those creators of world class popular fiction such as Michael Crichton, Umberto Eco, Steven King, Robert Ludlum, and John Le Carré, to mention a few, whose names have taken on the character of a trademark closely linked with whole genres of literary production. Here too, the effects of our new information/communication systems are changing what it means to be an author, only in this case, the status of successful individual authors is enhanced rather than reduced. They become larger than life, and no less super stars than the performers who act out their works in blockbuster Hollywood films. Their names alone are enough to conjure up generic worldviews and perspectives on the human condition. Paradoxically, however, it is precisely because of this situation that such authors also suffer depersonalization, in the sense of becoming the brand names for their particular products.

Of course, the phenomenon of super star author is not without historical precedent. Examples from the 19th century would certainly include Mark Twain and Charles Dickens, who were celebrated in the popular press throughout much of the literate world. Nevertheless, there is a major difference to our contemporary super stars. Authors like Twain, Dickens and others like Henry James, always remained themselves as integrated, unitary individuals. Their public faces or images were not significantly different from their private faces, if only because their exposure to the public was limited by the scope of 19th century print media. And this has generally been true for authors throughout the first half of the 20th century as well. By contrast, our current information/communication systems have become vehicles for the multimedia merchandising of star authors, and the inevitable result is a type of depersonalization whereby the author’s public face stands quite distinctly apart from the private individual. What occurs here is a fundamental split between the author as a one-dimensional radio or TV sound bite, one who takes on a virtual identity more or less equivalent to his or her familiar genre of works, and, presumably somewhere beneath this commercial mask, the actual person, who may ultimately be absorbed by the mask.. In other words, super star authors, like film stars, can become hostages to their marketplace persona, entrapped in the apparent necessity to live up to whatever has become expected of them.

Furthermore, the irony of literary success is such that having once reached the point of becoming larger than life representatives of their genres, star authors may find themselves not only confounded by their commercial mask, but also by their status as producers of a successful brand-name commodity. And at this level, regardless of whether the commodity is toothpaste or science fiction or romance novels, the laws of product marketing set in. Any conspicuously successful product must always be defended against competitors offering cheaper, mass-produced imitations. Since publishers are notoriously aware of this, they accordingly pressure their star authors to keep ahead of the competition. But while this can be a workable strategy for publishers dealing with up and coming new authors, when established super stars are involved the whole affair may be inverted. On the strength of their brand name, top of the line authors can pressure their publishers to pay high prices for products that otherwise might not be accepted.

At this juncture, it is useful to reflect upon the traditional symbiotic love-hate relationship between authors and publishers, and how this has been influenced by multimedia merchandising. Although as a general rule, modern authors and publishers clearly are dependent one another, it is rare to find authors without serious complaints about their publishers and vice versa. Experienced authors typically pass to beginners on a whole litany of warnings about publishers who do not promote their books properly, cannot be trusted to keep honest royalty accounts, fail to keep books long enough in print, and try to make quick profits by discounting and remainder sales. For their part, publishers rail against authors for behaving like spoiled children who do not turn in manuscripts on time, refuse to follow the advice of experienced editors, and do not appreciate the financial risks of marketing their work.

Scholars such as Alberto Manguel, who have studied the history of books, however, point out that author-publisher conflicts only began to exist toward the end of the Renaissance. Prior to that time, when books largely served to preserve religious dogmas and pre-existing knowledge, authors were seen as scribes rather than as creative agents. The author, as such, only emerged as a significant figure capable of creating something new with a market value in the Renaissance era, where William Shakespeare stands out as an exemplary precursor of the modern super star. Noteworthy too, is that with the rise of such authors, there was a parallel rise in publishing, which began its long march from a hand crafted affair to a mass production industry.

The foregoing little gloss on history has been introduced to underscore the evolving, contradictory nature of author- publisher relationships that have now reached the point of endangering the interests of both parties. Thus, the survival and prosperity of contemporary mass production, mass media publishers depends on their ability to bring out as many books as possible with the least financial risk. The ideal strategy for this is to produce a low cost, standardized product that can be sold to a more or less assured market; namely, readers whose preferences can be easily identified and satisfied. And in line with this strategy, it is in the publishers interest to focus on specific literary genres, where the already established style and content of any given genre will be more important than the name of an expensive, super star author. To accomplish this, it is only necessary for publishers to recruit a crew of entry level and relatively disposable authors capable of following and reproducing the style and content “template” defining any specific genre. (Parenthetically, it may be noted that there is even a minor cottage industry made up of writer workshops, books and magazines aimed at showing novices how to approximate various genre templates.) The result can be seen at any large metropolitan or airport bookstore, where books are primarily displayed according their genre, with only occasional displays emphasizing super star authors.

It should be clear that when the publishing strategy described above is applied efficiently, it provides an apparently guaranteed path toward substantial profits. But since this strategy is based on the repetition and reification of specific genres, it is inevitably limited by the popularity of those genres. One of the more obvious iron laws of economics is that all product lines evolve and change, and popular literary genres are not immune. One need only consider the rapid rise of the magical realism genre created by Latin American authors, and the phenomenal success of the Harry Potter child witchcraft genre, to see that publishers who are unwilling to accept the risk of investing in the authors of new creative products, are likely to fall by the wayside. Accordingly, by maintaining a reified genre strategy, publishers may gain short term benefits at the expense of their longer term survival.

Authors, on the other hand, can only respond to the “tyranny of genre” in one of two ways: they can either struggle within it, attempting to rise above the crowd by introducing new variations on the established style and content, or try to push beyond it by creating an entirely new genre of their own. However, there is no clear boundary line separating these two strategies, since it is possible for an author to attain star status by following one or both, or by creating a new blend of two or more genres. But those who simply master an established genre and choose to remain working within it have been described in a 1979 analysis by Hesse as “valued pens.” That is, creative mediocrities who never develop a distinctive creative voice of their own, and tend to basically write the same book over and over again. By contrast, the most effective strategy for authors is to create a new genre representing his or her unique vision of the world as it is, or as it might be. This is easier said than done, of course, since even those authors who may have a unique vision or world view often lack the talent and discipline to transform it into a text allowing readers to participate in the world they have imagined. And yet there is a line of authors stretching from Shakespeare and Cervantes through Dostoevsky, James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway who stand as successful examples of the creative strategy. Their narrative inventions of the world properly mark them as culture heroes who have helped shape our modern consciousness of self and society.

The question is: what is the publisher’s role? The most naïve answer could be that they offer a quality trademark to the product. Nothing more deceitful as it hardly happens that the quality trademark of a book is due to the publishing trademark: it is represented by the scientific editor trademark, who may be an authoritative academician, a famous journalist or writer, or sometimes, an important reviewer. Therefore also the quality trademark is outsourced. Let’s try again: what is the publisher’s role? Another naïve answer, although more realistic than the previous one: the publisher can strategically give visibility to his catalogue through promotion and distribution. But most publishers do not practically have a distribution channel and do not promote their catalogue except for small niches that do not offer a real visibility, because they do not want to get any risk. According to the Italian Chamber of Commerce not even a fifth of those presenting themselves as publishers can be considered publishers in practical terms (cfr. Bendia and Barocci 2001). But there is another question, only big publishers (a very small number of the publishers on the market) have their own distribution and promotion network. The rest has a good but outsourced net and we can’t explain what is the function of the editor. Let’s not give up and let’s ask again what is the publisher’s role: they put (protected, as in the case of school or university books, or a little bit elastic as for the fiction) the largest quantity of titles in their catalogue with the least economic effort and risk, improving profits and reducing the transaction costs as much as possible. This answer appears more functional and realistic but another question arises: what is the most suitable strategy for this purpose? Definitely a low cost standardized line of production that can predict the market tendencies, that is to say a kind of book whose readership can be easily identified, reached and pleased. This means, using the same exact words Carla Benedetti [1999] in her excellent “L’ombra lunga dell’autore” used, that publishers are interested into a specific literary genre where the name of the author is not really important as the genre determines the style, the content and the formal features of the fiction (this is the case for Romantic novels, detective or erotic fiction we can find everywhere, from railway station to airport bookshops) This phenomena concerns what was considered high culture not a long ago: fiction and non-fiction. Cognitive proletarians sometimes write books with no identity, assuming they are scientific academic works, churning them out as in an assembly line, stating they are the result of a research teamwork only to obtain government financing. This goes against the basic right of the reader according to which “ the freedom of writing does not mean that someone else is forced to read” as Daniel Pennac has brilliantly written in his “Come in un Romanzo” [1996].

Looking around in very important bookshops (Hugendubel, Barnes & Noble, Borders or Feltrinelli) I noticed the triumph of the literary genre over the author, as fiction (especially detective stories) are written by more than one author.

In this literary scenario (completely based on genre, standardization and low cost second-rate products to be sold in airports, railway stations, book shops and holiday resorts), what the author, apparently bound to become unnecessary, is going to do? He becomes a superstar, the true creator of his own work in such a way that, at first glance, might appear paradoxical. This paves the way to a problem of method. As a matter of fact, if the dialectical method is adopted, those reversals and inversions that occur when the use of a social medium is brought to the extreme consequences, are not considered. The dialectical method makes the author disappear, the spread of the “literary genre” reverses the scenario and changes the author into the superstar of the publishing market as the theory of McLuhan on the analysis of the publishing teaches.

Michel Foucault (1996) deals with the disappearance of the author too, but he does not only talks about technical reproducibility or standardization. He follows his “archaeological” method and builds a binary code: author first name/author’s name (1996:7). He hence starts a process of differentiation between the author as a person -in flesh and bones- and the author-public name as a trademark of a piece of work.

We can also make a difference between what the author has written, sorted out, re-arranged and published during his life and what he has taken notes of during his life (including when he makes his laundry or his shopping list) and that others, after his death, sorted out, re-edited and published under the name of “complete works by…”

No author “would survive” if his public name was associated with his author identity.

Foucault dismisses then the author as a physical person and devotes his attention to the author as function.

The scholar from Poitiers writes:

“The function author is linked to the legal and institutional system that takes, determines, and addresses the universe of the discourses. It does not influence, in the same way, all the discourses during the different ages and all sorts of civilizations. It is not named through the simple attribution of a discourse to an individual, but in a variety of specific and complex procedures and it does not simply refer to a real individual: it can simultaneously generate diverse egos and many position-subject that different classes of individuals can hold” (Foucalt 1996:14).

Foucault’s reflection -removing the author as a physical person- sets a further binary code:

- the author as a virtual identity that becomes a cult leader in an evolutionary process that creates a magical critical mass (Gerken,1996), fascinated by an individual virtual identity although “other”, compared to the author as a physical person (it’s in some way what happens to Hollywood movie star).

- the author as a collective, abstract, and impersonal identity, built on paper as an industrial product with no reference to any physical person (see Luther Blisset), concept that does not work well in publishing and that does not exist in the star system (Jessica Rabbit represents the evolution of the image of Rita Hayworth and the same for the very virtual Lara Croft, a sort of techno identity of Angelina Jolie).

This binary code is not strategic, following Foucault theory, because, what makes the difference for the authentic function/author is to be able to generate discursiveness, to establish an indefinite prospect of the discourse, even very different and gradually independent from the discursiveness itself (cfr. Foucault 1996: 15).

As to my paper, this binary code makes the difference, as it paves the way to the functional differentiation among “authors, earlier adopters, valued pens and ghosts”. I will talk later about this differentiation that contextualizes the subject of my paper in the current scenarios of glocalization1. where all these four personalities, can generate discursiveness as to the context, or going back and forth in space and time.

We only have to think about those theories (and function/author) that have mastered certain ages but that have now disappeared, and about those theories and function/author once considered minor but not anymore (Schopenahauer, Simmel and many others). We cannot exclude, for example, that Harmony or Bluemoon collection can be considered as the epistemological basis of the family sociology of the twenty-second century and beyond. After all, isn’t it true that the history of the modern Western political thought is based on a pamphlet written in a rush by someone who wanted to use it as an instant book and self-help manual for high-flying politicians and, in the same time, the author wanted to be a political counselor even more high flying than these politicians? Isn’t under these circumstances that “Il Principe” was written? And isn’t it funny that most of our so called political experts are disgusted and horrified by instant books, not disdaining to write them when they are going to retire?

In order not to loose our concentration, it is appropriate to have a look back.

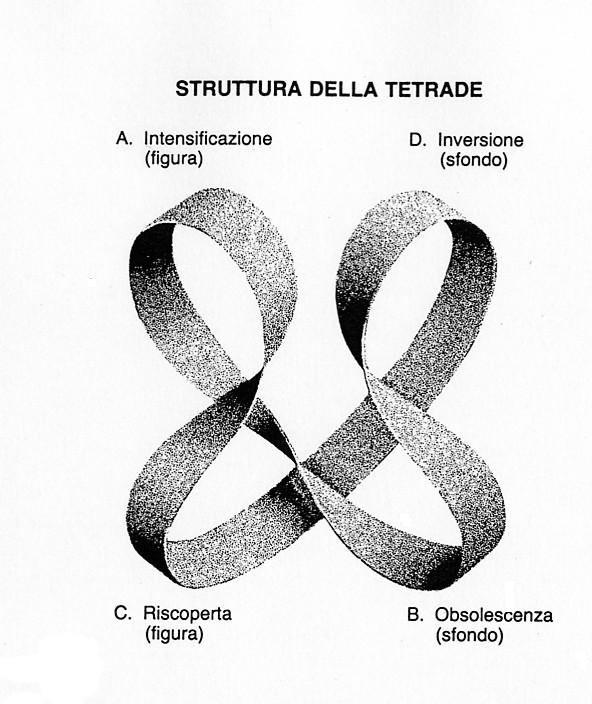

To grasp the age leap represented by the glocalization in the publishing field, it is useful to remember the tetradic method shown by McLuhan [McLuhan – Powers 1989] where the Canadian scholar explains the function of the reversal of a media if brought to his extreme potentiality.

STRUCTURE OF THE TETRADE

A. Enhancement (picture)

B. Obsolescence (background)

C. Retrieval (picture)

D. Reversal (background)

In such a literary scenario, ruled by the genre, the only one who can stand out on publishers and editors is the author, whose works have their own original specificity and where the different genres mix themselves, enslaved to the author’s creative talent that becomes a worldwide trademark, and consequently a global phenomenon. Practical examples? Michael Crichton, Robert Ludlum, Umberto Eco. The author, as a globalized trademark, identified thanks to his talent and style at reader’s eyes who finds him unmistakable (and if an author is not unmistakable, He is not considered an author, he can just be considered a valued pen or, even worse, a ghost), shows himself as the creator, the inventor and the motionless engine that physically generates and emits the life breath of his work. This latter is usually finished by his “slaves” that carry out the basic researches, get information and prepare the archive and write the first drafts of chapters or a paragraphs, maybe not essential but useful to the overall harmony of the text. The difference between a cognitive proletarian of a publishing assembly line and a “slave” consists in their level of evolutionary self-consciousness. The cognitive proletarian (mainly the “ghost” as we will see later) believes he is an author while the “slave” is well aware he is an office boy or, at most, an ordinary worker with no identity, that’s why the proletarian risks to fail more than the “slave” who is aware of his working state.

The consequence is that the small or medium publishing houses are going to implode thinking the local literature can help to create a small niche to purchase just a few “ethnic” books, compared to those that a small-medium publisher might wish to show in his catalogue. Therefore, local, ethnic and niche readers (very qualified and acquainted) can buy copies from a selective, high quality and expensive catalogue that can be handled only by those few, small-medium, high quality publishers, which can be considered very good for public relations, but too few to be statistically negligible. Expensive books, yet, do live long on the market unless they become paperback editions, which is not suitable for a small-medium publisher who can hardly find a channel for distribution. This explains why small-medium publishers’ invisibility makes them unattractive for emerging writers that consider them as entry publishers, (a choice that would undermine the credibility of the small-medium publisher to the eyes of his qualified readers). Being an entry publisher and a quality publisher, at the same time, is nearly a contradiction in terms. The medium level publisher would survive fairly well through the mechanism that associates outstanding editors and genres writers that work as cognitive proletarians. Bookstalls, railway station or airport bookshops represent the rightful prêt-à-porter of the publishing market.

High literature (in a wide sense, of course) could take advantage of this situation: that kind of literature where the author represents his own trademark as an absolutely unmistakable creative and original specificity, becoming the fathers of the Zeitgeist of twenty-first century. The creative entity that conceived, designed and thoroughly developed a “product” protects his patents, trademarks and copyrights and promotes strategies, public relations and the marketing of the “self” [Seidl and Beutelmayer, 1999]. The author is then a resource that can be both highly strategic and not easy to find and highly strategic and easy to find, talking about those who are able to revise the master’s work and not just to reproduce it in a manneristic way. Others risk to became cognitive proletarians or, as it is fashionable now “cognitarians”.

There are two kinds of cognitarians:

- The valued pens [Hesse 1979];

- The ghosts.

The valued pens are those writers that we call authors, although it is not the appropriate term because they keep writing the same book for years. They first write, for example, “Goethe during a journey” then “Goethe at home”, then “Goethe in the kitchen” and then “Goethe in the living room” and so on, rewriting something that does not offers any cognitive-exploratory chance of literary knowledge.

The ghosts are all those who write without an identity or right to sign their works: they write technical manuals, speeches for politicians, and can be considered “slaves” for well-known writers who are usually considered valued pens. Even those who ideologically do not agree, at least formally, with the of the strategy author/brand as intellectual property (registered trademark and copyright) avoid it: this may be the case of Naomi Klein and her book Nologo.

She represents the no-global movement (www.nologo.org) in its empty ideological form, but global in its evolutionary strategies. The very same movement has created a logo (Nologo) and promoted a global strategy, in order to set itself against the alleged capitalistic and globalizing domain of logo and brand… That’s life.!

| HIGHLY STRATEGIC | BARELY STRATEGIC | |

|---|---|---|

| HARD TO FIND | Authors | Valued pens |

| EASY TO FIND | Earlier adopters of the authors | Ghosts |

The author as an intellectual property (patents, trademarks, copyrights etc.) has sound national legal foundations [De Guglielmo, 1999, www.siae.it] thanks to on line certifications, as in the case of Sresa [www.sresa.com], (updating about copyright in the multimedia and virtual circles [Sirotti Gaudenzi, 2003] and international ones [Ilardi, 1999]).

To understand their evolutionary and strategic power, it is necessary to place the author and the intellectual property in a process of differentiation and reconstruction of personal and social identity characterized by four crucial circular steps:

1) Self designing the identity considering the author as a stranger [Pitasi 1994] in the globalized life where everything is possible with the ensuing risks and opportunities. Therefore the author becomes an identity only if he tries to experiment, to survive a kind of Orteghian shellfish [Ortega y Gasset, 1994]. If he changes the uncertain and floating situation which also concerns his community (in terms of practice, interests etc. and this community can be geographically connoted only by chance). We could describe this as the connotation step.

2) Thanks to the differentiation between the law and its capability to capitalize [De Soto 2001, Luhmann 1990a], the author becomes the person who legally and financially converts him into a trademark and future wealth, developing procedures to protect the intellectual property [cf. Stewart, 1999]. This step is called capitalization.

3) Thanks to these procedure knowledge can be shared and easy to develop through the e-learning system generating dynamics of connective intelligence. The creative and legal specificity of the author is characterized and differentiated through a technological and combined use of the media as devised by Foucault - password, user id, selective accesses, technical revision of a document -. The most important thing is to standardize these processes, not just from a legal point of view [Imai, 2001]. This is the technological standardization step.

4) After the three phases above mentioned, the author starts his process of glocalization, that is to say he sets up those dynamics to create a community of elective affinities. He produces micro culture, self-produced and self-selected microcosms that form this community and the critical mass of the author. We could call this final step selective glocalization.

OCTS is the acronym of the four-steps process.

This is an anthropological process developed by those mechanisms of differentiation that consider law as a subsystem of the society, functionally differentiated by the binary code right/wrong and by the program of the provisions in force [Luhman, 1984]. The system is autopoietic and self-referential and it evolves into the three-steps process of: variety, selection and stabilization [Luhmann, 1990a] where truth and justice have disclosed long ago their relativity and their being multiform. These mechanisms show a deeper and more complex socio-cultural change representing the, unfortunately denigrated, inheritance of Cervantes [Kundera, 1988]. When Don Quixote leaves the house, the world is already a circus of relativity where good and evil, true and false, right and wrong are undistinguishable. Possible things go beyond what can be made and the urgent need of selectivity shows itself powerfully …but how? At that time, the post-modern had already started to pave the way to the story of the novel, where every piece of writing became a quite relative new exploration, interpretation, reconstruction, through which an observer created his world without any pretensions or universality. Every observer ( the reader and especially the author) became a personal reader [Hesse,1979] trying to develop his evolution.

Voltaire (especially for his philosophical novels such as Candide and Zadig), Jan Potocki (expressing his genius in Manoscritto trovato a Saragozza), Luigi Pirandello and Italo Svevo (even students who just red summaries of their works can understand what I am talking about), and Arthur Schnitzler (important writing such as Al pappagallo verde and La contessina Mizzi) can be considered personal readers. Milan Kundera believes that the degree of wisdom of an individual and/or a society is measured by their power to resist to symbols [Kundera, 1988 ].

The author is someone who harmonizes epic and lyrics in his cognitive approach towards the world. Epic, as he is fascinated by the world and its variety he can jump into, lyrical because, observing the world through the lens of his referentiality, the author re-invents it according to his own pattern, his own ideal. The observer/author observes the variety and, more or less rationally and consciously, makes a decision generating adventures (as meant by Simmel) which come to life and become the vehicle of stabilization of the personal and social identity of the observer/author. The world seen as a variety, plays a vital role. The world seen as collective imaginaries and overwhelming symbols is gradually dissolving thanks to Cervantes’s heritage. But something does not sound right: the author keeps moving ahead with no fear (or hope) in the evolutionary molding of his self-referentiality, but those who do not hold the evolutionary features of the author how can they handle the process of variety/selectivity/stabilization?

Here comes in what is beyond dispute during the XX century: fear. The intellectual capitalism presents four kinds of human resources:

- Highly strategic and hard to find: the authors

- Highly strategic and easy to find. The best follower among the earlier adopters and interpreters of the authors.

- Barely strategic and hard to find: the valued pens.

- Barely strategic and easy to find: the ghosts.

The author is the one who auto-referentially applies the OCTS process without fear or hope towards the world. The four categories mentioned above must face a probable and relevant kind of fear. It is the unbearable lightness of being of those who are aware that they are living on a peripheral planet in a peripheral galaxy with no master, or guide or meaning. Let’s go back to a previous point: Milan Kundera believes that the degree of wisdom of an individual and/or a society can be measured by their power to resist to symbols [Kundera, 1988). Fragile people hardly resists to symbols because the symbolic power of an abstract, universal and certain discipline is reassuring for an individual and under the appearance, one can see the possibility of life, the experimental selves hidden behind the impersonality. Here comes in, with his irreverent humor and the irony of his work, Franz Kafka [Kundera, 1993 pp.193-229].

As Kundera stated: “for Kafka the institution is a device that abide by its own laws and no one knows when and by whom they have been planned. These laws have nothing to do with human interests and thus are not intelligible.”[cf. Kundera, 1988 pp.145-146].

This reminds us a selective system based on the right/wrong code that stabilizes itself through the program of the current provisions (Luhman 1984, 1990a, 1990b): the Kafkian world becomes the place where the pseudo-theological language of the glorification of the power becomes a reality: law. It turns out to be simply a shape, the communication shape of the power and not an alternative to it, nor even an abstract and universal tool to control the real power of natural and/or juridical persons. Before Kafka’s works, other literary works dealt with and criticized the institutions, explaining and developing the mechanism of the guilt that looks for the punishment (as in the novel “Crime and Punishment”). With Kafka complex mechanisms full of humor and irony come to sight, in order to give sense to a mechanism that would be otherwise spine-chilling in its ironic nonsense that represents the essence of Kafka’s world. [cf. Kundera, 1988 p.148]:

- The punishment looks for the guilt;

- The punishment finds the guilt;

- The accused looks for his guilt.

A modern reader catches individual fear and anxiety in Kafka’s pages, before the overwhelming society with its totalizing institutions. Those who can understand the irony and the humor of the accused that looks for his guilt and that circus of relativity already sensed by Cervantes, revealed by Kafka and formalized by some deconstructionalist and postmodern law theories [Minda, 2001], can focus the non-sense of fear as shape of the non-sense of hope. This is where the theory of novel takes the law theory in his hand (in its functionalist-luhmanian version, cf. February, 1975 and 1990) getting to an apparently weird interpretation that also implies powerful heuristic and practical implications. They are essential to understand the formal identity of the author as intellectual property and trademark strategy in modern information society. The evolution of the novel represents, at the same time, a break-up and a widening of the hermeneutical multiplicity of human things, the mere recollection of the past, the ordinary stories as well as the myth of the future. The development of the novel gives increasing inner life and psychological dignity to the characters who are formalizations of different and relative imaginaries. The relevance of the ego-character (who represents a problematic exploration of an aspect of life), is in inverse relation to the entire world population, or in more sophisticated words to all the possible varieties that an observer (in this specific case the reader) can select. At the same time, the reader’s ego specific gravity is in inverse relation to all the possible interpretations potentially selected by another observer who is observing the first observer watching the ego-character. The drama metaphor prevails, and one can assume different levels of observation as in Escher works (www.mcescher.com or http:www.cs.unc.edu/~davemc/Pic/Escher), but this is not the main topic of my paper.

Just as the ego-character of the theory of novel, the ego-person (in this case the physical one) of the law theory goes through a gradual process of overworking, characterized by grotesque implications. When Democritus develops his philosophy, he represents 1/400000 of the whole humanity while any modern researcher embodies about 1/6000000000 of the whole mankind and the relativeness of his thought, his work and his life. Not only the ego-character, but also the ego-person, becomes lighter and lighter, ephemeral and relative and this lightness becomes, sometimes, as already mentioned, unbearable. This is true also for the juridical persons: in one way the institution is seen as an apparatus, in another it shows its precariousness and weakness. The institutions can still overwhelm the individual but they can’t guide and direct him. The ego-person discovers then the relativeness of the institutions and his loneliness in the universe [Pitasi, 1991]. In this context, the author, the novelist as well as the scientist, is the person who does not reproduce reassuring life patterns (myths, rituals, ideologies etc.) with illusionist and deceptive soundness and heaviness (as in Kundera’s terminology), but he is the one who creates an evolutionary “strategy” of exploration and subjective reconstruction of the ego-person’s existence, so that he can appreciate both the relativity of his ego and the potential specificity, making it topical of his self reference. The author, after having created his high concept [Tintori, 2001], legally developing a trademark and a marketing identity, turns into the person who tries to give added value to his specificity still being aware to be simply one six billionth (at least nowadays) of humanity. The ensuing procedure develops through the OCTS process while his legal identity is the more sophisticated and protected, the more the author can play with the pseudo-theological language of the law: the author learns the rules of the game (analyzing the current prescriptive framework as a systemic program within the code selects right/wrong) to open the game of the rules, re-inventing them on the base of the strategic-evolutionary guiding principle of his self reference.

1 References

Cavalli-G.Fioretti, S.P. Come si fa l’editore, Ed. Bibliografica, Milano,ultima, ed.disponibile

de Guglielmo, A. Diritto d’autore diritti connessi,T.de Guglielmo Editore,Milano 1999

de Soto, H. Il mistero del capitale, Garzanti, Milano 2001

Ferrari, V. Funzioni del diritto,Laterza, Roma,ult. Ed. disp.

Formenti. C. Not Economy, Etas,Milano 2003

Foucault, M. La verità e le forme giuridiche, La città del sole, Napoli 1994

Foucault, M. Il discorso,la storia ,la verità, Einaudi, Torino, 2001

Friedmann, D. L’ordine del diritto, Il Mulino, Bologna 2004

G.Cocchetti, M. L’autore in cerca di editore,Ed. Bibliografica, Milano,ultima, ed.disponibile

Hesse, H. Una bibliotecadella letteratura universale, Adelphi, Milano 1979

Ilardi, A. Manuale dei trattati di proprietà intellettuale, Zanichelli, Bologna, ultima ed. disponibile

Kundera, M. L’arte del romanzo, Adelphi, Milano 1988

Kundera, M. I testamenti traditi, Adelphi, Milano 1993

La Spina, A. Politica per il Mezzogiorno, Il Mulino, Bologna 2003

Lessig, L. Cultura libera,Apogeo, Milano 2005

Longo, B. La nuova editoria, Ed. Bibliografica, Milano,ultima, 2001

Luhmannn, N. La differenziazione del diritto,Il Mulino, Bologna 1990

McLuhan, M. Il villaggio globale, SugarCo, Milano 1989

Mitnick, K.D. L’arte dell’inganno-i consigli dell’hacker più famoso del mondo-, Feltrinelli,Milano 2005

Ormezzano, A. Codice dell’editore, Ed. Bibliografica, Milano,ultima, 2002

Ortega y Gasset, J. Goethe, Medusa,Milano 2003

Ortega y Gasset, J. Meditazioni sulla felicità ,Sugarco, Milano ultima ed. disponibile

Pennac, D. Come un romanzo, Feltrinellli, Milano 1996

Salvagni, C. Marchi, Brevetti e know how, Finanze e Lavoro, Napoli 2003

Sirotti Gaudenzi, A. Il nuovo diritto d’autore, Maggioli, Rimini 2003

Unseld, S. L’autore e i suoi editori, Adelphi ,Milano1988

Unseld, S. Goethe e i suoi editori, Adelphi, Milano 1997

Vizinzczey, S. I dieci comandamenti di uno scrittore, Marsilio, Venezia 2004