Telling stories about story-tellers

Contando historias sobre contadores de historias

- Tomás Ibáñez Gracia

- Lupicinio Íñiguez

- Rex Stainton-Rogers

- Narratives

- Reflexivity

- Social constructionism

- Rex Stainton-Rogers

- Narratividad

- Historias

- Construccionismo social

Rex

—If it is true that, in Beryl C. Curt’s terms, story-tellers are “reality-makers” then...

Interrupter: I beg you pardon but I think you are beginning your talk quite badly. I thought you were sceptical about true narratives... But I am sorry, I should have presented me before interrupting you so abruptly.

—It doesn’t mind, you are not a foreigner for me. I think I know you since 1994, when Textuality and Tectonics was published. Obviously enough, you are the Interrupter. Arent’ you? Well, I expected some Berylian kind of interference in my talk, but I did not expect it would take place so early! Anyway, I must concede that you have a point. So let me start with a new beginning with no reference to “truth”.

If it seems convincing that, in Beryl terms, story-tellers are “reality-makers”, then to tell stories about story tellers is also the way to make them real. What follows from this is that, in order to avoid the strange pitfalls of a reality made real by agents who are not themselves real because they have not yet been “storied-into-being”, we have no other choice than to tell stories about story-tellers. Since I am so fond of the kind of reality “storied-into-being” by Rex Stainton-Rogers, I will do my best to help keeping alive this reality by “making real” its maker, and it is why I am delighted to tell here my own particular story about him.

Interrupter: Excuse me again, but as being myself a part of Rex, me the Interrupter, of course, I must say that I knew Rex long before you, and I can tell you that he did not wait to your particular story about him to be “storied-into-being”, we are all “storied-into-being” as soon as we enter in a language community. But, maybe, I did not catch exactly your argument...

—You are right. You did not quite catch it. I am not speaking about Rex Stainton-Rogers in general terms, but specifically about Rex as a story-teller, and this makes all the difference. But please, be so kind to give me a chance, let me construct my narrative and try to keep silent just for a few minutes. Okey? Nice!

Yamaa El Fna

Well, some years ago I travelled to Morocco for the first time in my life. A hot summer sun was shinning and I was wandering about the streets of Marrakech when, suddenly, I was caught in a vertiginous swirl. I found myself swinging in a strange and troubling dance composed by a blend of vivid colours, people, perfumes, animals, music, and above all, a continuous stream of story-telling activities. I was at the centre of the mythical Yamaa El Fna square, the living monument that the living monument that Marrakech constructs every day to honour oral culture. Oh! I see that you have found a new way to make interruptions! It is a silent one, but it is very efective, indeed, to distract the attention of the audience from what I am saying. I wonder what your next trick will be... Yes, I was at Yama el Fna, and... With a sense of full certainty I knew immediately that I had already been there in the past. Morocco’s bright sun was not there, neither were present the vivid colours, the animals and so on, but it was exactly the same magic which was working. And suddenly I remembered: it was in Budapest, some years before my Marrakech trip. The “Barcelona brigade” had decided to attend the general meeting of the European Association of Experimental —yes, “experimental”— Social Psychology. The fact is that we tried very hard to get excited by what was going on in the different academic sessions without, may I say it, any success at all, until we landed in a peculiar one. It was a session where the well-known “Yamaa El Fna effect” predicted by a skilful experimental social psychologist was confirmed at point 0.00001, at least. What seemed, at first glance, to be an “ageing hippie” was telling a story about “social constructionists as raconteurs”. When he stopped talking, the “Barcelona brigade”, which was almost the unique audience in the room, started clapping enthusiastically. It was the beginning of a long standing friendship, as someone said in Casablanca, another well know Morocco city.

Casablanca

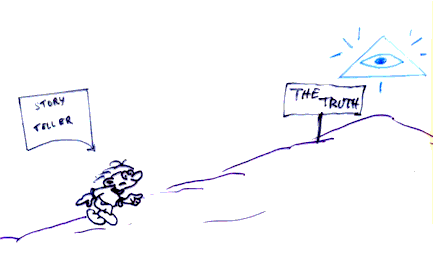

Story telling is, as we all know, one of the oldest mankind tradition with emblematic figures, like Homer for instance. But, besides such great reality makers as were Homer or Plato, a large amount of people went busy in making clever stories to diffuse practical knowledge, to foster ethical reflections, to promote wisdom, or to stimulate people imagination and so on... Unfortunately, as it happens too often with human beings, a concern with competition began to spread among story tellers. They became sensitive to such questions as: who could gather the bigger audience, who could gain more prestige, who could tell the more convincing stories and, finally, who could manage better the “power-knowledge synarchy”. Therefore, story tellers began to climb, progressively, the slopes of the surrounding mountains to stand above the other story tellers. Step by step they climbed so high that they reached the stern regions where “the truth” inhabits, indeed, a place very close to the place where it seems that God used to stand.

The story teller

Strangely enough, from above the highest ladders of the story-telling hierarchy, not any story could be told any more, for at these altitudes the air gets rarefied and talking, as we all know, requires the materiality of the air to propagate the waves of its sounds. No air, no sounds, no stories! Some story-tellers, the most of them indeed, felt quite happy with this new circumstance. At first moment, being so close to where God remains, they told people that if their own personal voice was no longer audible it was because they had stopped telling stories and they were offering now something infinitely less disputable as God’s word directly is. At a second moment, as they went more sophisticated, they changed their source of legitimacy from God to Science. If their own personal voice was not longer audible it was just because they were no more, and no less, than the neutral medium through which scientific truth was manifesting itself.

In terms of “power-knowledge synarchy”, this move was, obviously, genial. But some story tellers, like Rex Stainton-Rogers, felt quite uneasy in that rarefied atmosphere. They wanted to breathe fresh air, they wanted to recover their voice, and they wanted to stay where people are, that is, down the valley. For, like the “raconteurs” of Yamaa El Fna, story tellers need desperately to be among people. Stories, which know that they are just stories, cannot live a mono-polar existence, they cannot exist without the simultaneous existence of stories-receivers who give them sense by incorporating them within a large web of competing stories. As we can read in “Social psychology: a critical agenda”, stories never operate in isolation, discrete and adjacent plates of narratives, that is, tectons, can clash and grind together. On the contrary, truth does not need to be heard, its value rests on being discovered and declared. For when you start playing “truth games” and when you engage in displaying “true narratives” you not only loose your own voice, but you also jump automatically out from inter-textuality. No matter what other texts may say. If your text is grounded on a true description it cannot be otherwise than it is, it cannot stand as one story among other stories equally possible. You can forget the audience, for the value of what you have stated is self-contained, truth has been declared and this is worthy enough. Nobody can change your terms, unless, of course, if what you stated was not “truly true”.

Down the valley

Like the growing flow of story tellers who were walking down from the mountains, Rex Stainton-Rogers engaged in telling stories about this very peculiar kind of “self-denying” stories which told a strange story about them being not stories. This was, indeed, a savage attack on the very grounding of authority, for in asking why some stories refuse so energetically to be considered as such, what emerged to the surface was no more than the subtle mechanism of power games and the gears of “power-knowledge synarchy”. Michel Foucault had already warned us that the effectiveness of power is a function of what it succeeds to hide about its own working processes.

Interrupter: Stop just for a moment, please...

—Oh! I was beginning to be seriously worried by your silence, my dear. I both hoped and feared that you had fall asleep instead of being captivated by my talk.

Interrupter: Not at all. I must admit that I have always been fond of allegories even if the allegory of the mountain has already been used, as you know, in other kind of narratives. I was just feeling a bit uneasy with your metaphors about climbing and descending, up and down, high and low. Are you not just reproducing one of these hierarchical bipolarities that Derrida deconstructs so cleverly?

—Not exactly. I think that one manner you can subvert the power effects of these hierarchised bi-polarities is precisely by using them in an inverted value-locating way...

Interrupter: Yes, but to invert the hierarchy is maybe not the best way to challenge the logic of hierarchy.

—Maybe you are right but this point would deserve a long discussion we can have later, I had better turn now to my talk...

Interrupter: It’s okay with me. But let me add just one more point. Until now you have emphasised Rex’s concern with being a full-blown story-teller and this entails, for sure, a lot of subversive effects, but I guess there is more to be said about Rex’s agenda...

—Thanks very much for your help, for I was precisely going to say that to accept fully a raconteurial identity and to expose this identity in the sancta sanctorum of the European Association of Experimental Social Psychology as if one were at the Yamaa El Fna square, was not the whole of Rex Stainton-Rogers’ subversive craft. He promoted heresy just by standing as he wanted to stand instead of standing as he ought to stand. Maybe he had learned, when he was put in jail many years ago by Phillip Zimbardo, that you end up thinking as you dress. Anyway, he had decided to work over conventionality itself and thus, for instance, he did not make the slightest effort to look like a conventional scholar. As you know, one of the important things in being a full blown scholar is, precisely, to look like a scholar... to the extend that many scholars are nothing more than they looking like scholars. Some of them are so deeply satisfied by looking like a scholar that they can carry with them their scholar “way of life” all along their worldly life, allowing it to invade every one of their words and deeds. Their wife, or their husband, sleeps with a scholar; their friends always speak with a scholar; it is always a scholar who watches a movie or reads a novel or drinks a cup of tea. The “public-private” dichotomy is resolved by giving a hegemonic surface to one of its terms. Other scholars see their scientific activity as such a serious endeavour that they strive to save it from any risk of worldly life pollution. So they reinforce the dichotomy by tracing a clear-cut separation between academic life and every day life.

The scholar

To subvert conventionality in this field implies challenging the very meaning of the dichotomy and to show, in Beryl Curt’s terms, that “there is no point at which we cross over from academic life into real life”. You can challenge the dichotomy by telling a story about the consequences of splitting the professional and the every day life into two separated realms, but Rex did something more than that, he lived practically the story of professional and worldly life entanglement. As an undifferentiated part of his life, he conducted his academic activity just as he conducted his life. Obviously enough, this “confusion of genres” did not convey an appearance of seriousness. But who has stated that to do a serious job, or to handle a serious issue, you have to look serious yourself, or you are to take yourself seriously? Why should you conceal the pleasure you take in doing serious things and why do you have to avoid pleasure on doing them? Moreover, why should you abstain from doing the serious things you work in, in such a way that this working itself produces pleasure? When stories are well constructed, they produce always a “listening pleasure”, even if they deal with dramatic issues. But when the story teller is a good one, the teller himself takes pleasure in the telling. You cannot be a “constipated” story teller for if you have not taken pleasure in making the story, the story will simply not work. As you know well enough, we have always been told not to mix pleasure with work, not to have fun in the knowledge factory. We have been told the story that to reach the scientific heaven we have necessarily to walk along an ascetic painful, self-sacrificing and tough rocky road.

Interrupter: Yea. One per cent of inspiration and 99 per cent of transpiration, that is what is needed to conduct a good research. Well, social psychologists have produced a lot of data to show that a good is valued if you have to strive for it and that it loses all its interest if you reach it too easely. So, if you want your work to be appreciated you have to show that it was a hard one and that you did not do it for your own pleasure, or “with pleasure”.

—Yes you are right and it is precisily why laughing when working subverts the work, unless, obviously enough, you are a movie actor and your laugh is in the script. But the script of “power games” exclude humour and irony as if they were the very devil in person. I will never forget the tremendous subversive force of Daniel Cohn Bendit jovial and hilarious visage, standing face to face with the tense sour, and, of course, helmet protected face of a frightening policeman. Humour, irony and laugh are strongly effective convention-dissolving devices, which work as mortal weapons against all the power games. No doubt that you have already guessed that humour and irony were so deeply embedded into Rex’s practices that they followed him to wherever place he went. Indeed, irony was part of his political agenda.

Cohn-Bendit

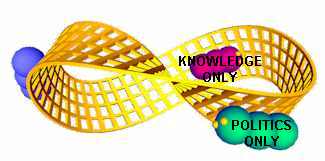

Interrupter: Don’t tell me that you are going to deal now with political issues! If you introduce not only fun in the “knowledge factory” but also politics it will stop being a factory and maybe it will stop keeping any relation at all with knowledge! Don’t you think that “political agendas” are best to be kept outside science and far away from scientific knowledge issues?

—Not at all. To separate politics from knowledge is, precisely, to take a strong political position. Believe me, if you are to make a political commitment, it seems better to know that you are doing so. Having to choose between ignoring that he had a political agenda or trying to hide it, or finaly to think about it and to expose it, Rex decided that the best thing to do was to think and to talk explicity about his political agenda. It was a political agenda which was fully aware that discourses and stories are not “free-floating entities”, but that they are enmeshed in a complex web of power structures, power relations and conflicting interests. This entails, at least, three consequences. The first is that story telling is “always already” politicised, in the broader sense of the term “politics”, for it is a practice which impinges upon the power games which are working inside a society and within a culture. The second is that story telling is fed by the long lasting history of domination and resistance discourses and practices which have sedimented into the large web of meanings from which people construct their ways of thinking, their ways of being, their ways of doing, including of course their story telling practices. The third is that story telling produces political effects insofar as it helps, simultaneously, to silence, or to empower, other stories depending on what political soil they are grounded.

So how could story tellers pretend neutrality, even if they decided, for instance, to stop telling stories? But it is part of some political agenda to claim for neutrality as it is part of other political agendas to show that no discourse is value-free, neither in its contents nor in its effects. A political agenda does not need to foster or to warrant any particular political location to be a full-blown political agenda. It is widely enough, and even, if I dare to say it, much more deeply political, to set on this agenda a strong concern with promoting politicising practices. For political locations are usually resting places where one finds ready made responses to political issues, whereas politicising is a practice which asks for the construction of responses once an issue apparently alien to the political realm has been re-written in such a way as to make apparent its political texture.

Moebius

Curiously enough, this refusal to promote or to accept for oneself any precise political location locates you in a pretty well-defined political position. The position of those who struggle against the present and the future forms of domination, the position of those who foster resistance to power games, the position of those who strive to subvert the established rules of the game.

Interrupter: Stand there! I am sorry to interrupt such a passionate discourse, but what is all this talk about “the present and the future forms of domination”?! Maybe you are in possession of a crystal ball which allows you both to foresee the future form of domination and to be sure that you are already opposing them?

—Oh, dear! I don’t understand how Beryl could stand you all along a whole-book-length story! He was a saint! Let me confess that I have no crystal ball. What I meant was just the contrary of what you are implying. It doesn’t matter which form of domination it will take in the future, for the subversive effect of “politicising” in the sense this term has been used here is precisely independent of the specificity of domination forms, its strength lays precisely on that it is not a weapon directed against one particular device of domination. This is why I spoke of the future, just to make it clear. But it seems that I failed in my intention.

Interrupter: Well, intentions are not always transparent. By the way, to mention such a mental activity as “intentions” makes me thing that maybe you are implying some psychological strain to oppose authority...

—Not at all. To account for this kind of positioning, I mean a subvertive positioning, you have to search for neither a personally well-established credo, nor an inner motivation or a peculiar mental disposition. It is just a plain effect of politicising practices themselves, for the stories which need to hide the power mechanisms upon which they rest are usually the stories told from a dominant position. This is, as you know so well, my dear Michel Foucault, a condition for their effectiveness and if you weaken this effectiveness you are, you like it or not, on the other side of the barricade. By the way, I guess that Rex Stainton-Rogers liked it very much. As a part of the Beryl Curt’s complex, he took a special care not to be a “true believer” in any old or new faith, and even less, a missionary of any credo. He stood just at the opposite, using a full blown agnosticism to rise suspicion over all God-games over all truth games, over all power games, over all stories, including his own stories. He was, in Beryl Curt’s terms, always “searching for new stepping stones”, instead of dreaming with “a harbour which would save him from thinking”.

Where is now Rex Stainton-Rogers? He is not in Yamaa El Fna; neither in Budapest, nor in Barcelona. It is useless to look for him in any precise place, not even in any individualised image, for he is, plainly, a story. A story which has succeeded in sedimenting within a collective endeavour. A collective endeavour which is busy in changing the agenda of old questions. Not to ask any more “What is life?” but “What life do we want to live?”. Not to ask any longer “Who are we?” but “Who do we want to be?”. Not to be anxious about “What is the world?” but “What kind of world do we want?”. Definitively, the best way to laugh again with Rex is to propel this collective journey in full sail.